In this episode of You’re A Better Artist Than You Think:

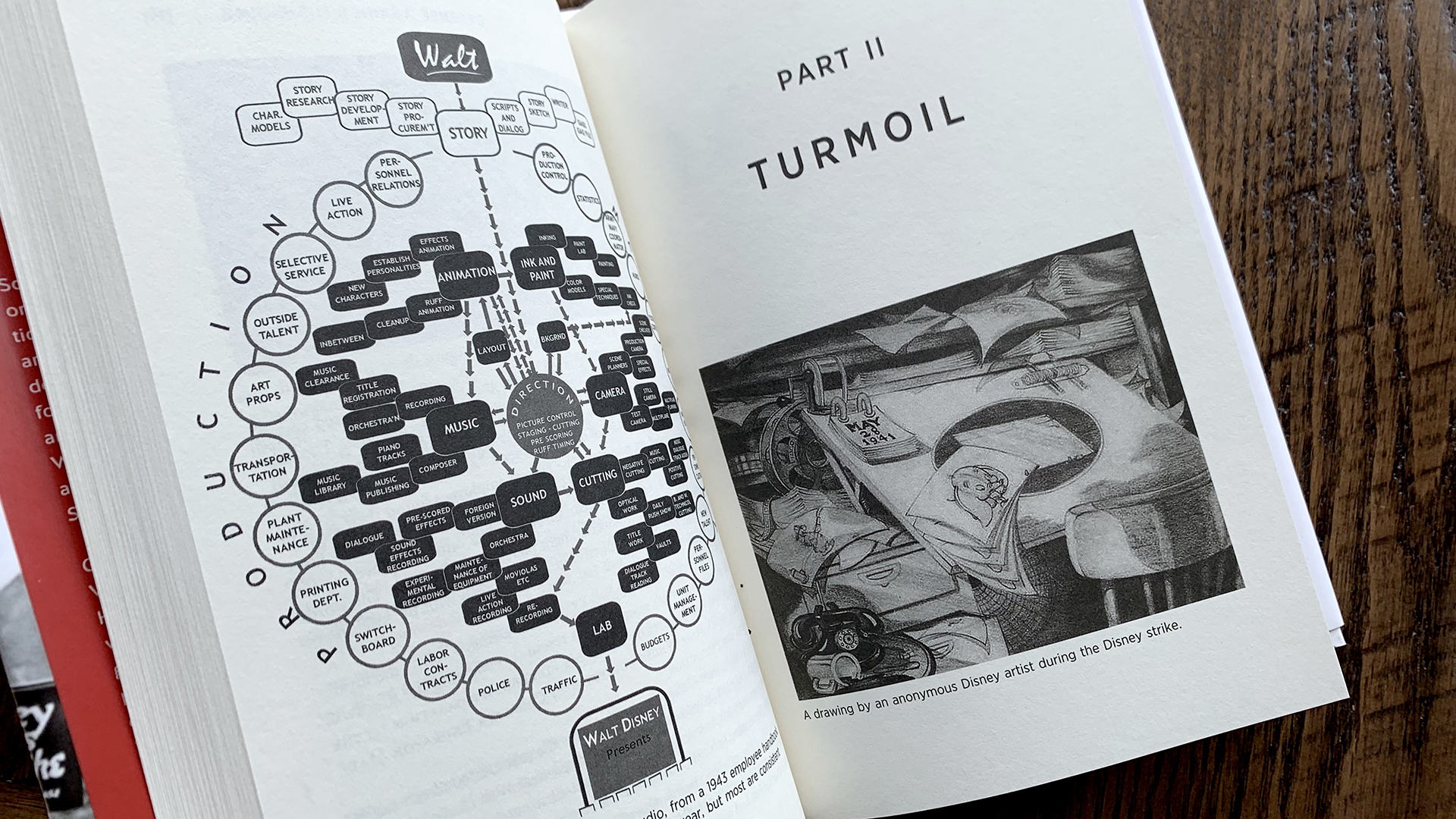

The Disney Revolt author Jake Friedman surveys the infamous Disney animation strike of 1941 and explains why it matters to present-day artists.

We consider the cost of Walt Disney’s perfectionism, the painful, personal consequences of his decisions and whether he ever learned from them…

PLUS: The most influential Disney animator you’ve never heard of…

How To Listen:

Listen to the interview via the YouTube player below, subscribe to the audio podcast (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, Email) or read on for the transcript…

[UP NEXT: Interacting with COLOR!]

…Or Read The Transcript:

Chris: Jake, what was the Disney strike of 1941?

…and why does it matter to professional artists in 2024?

Jake: There was a big surge in unionism in Hollywood.

Each craft: The screen actors, screen directors, screenwriters, projectionists, camera operators, background painters, office workers, so on and so on…

Each one had to fight for the right to have a union in each studio.

The “Screen Cartoonists” (a.k.a. “the animators”), were the only craft in Hollywood without union representation.

Then suddenly, starting with MGM in 1940, one by one, the major studios began to accept union presence for the animators.

And after MGM, you know, we have Paramount, Universal, finally Warner Brothers, and at the very end of this list is Disney.

Disney being the last studio to withhold union representation for the animators, which was the last craft in Hollywood to have a union.

So, they’re fighting for salaries that are at least equal to those at MGM and these other studios.

You know, these are people who are proud for having animated Fantasia, or being inkers and/ or painters for Pinocchio.

…and why are they earning less than the same jobs over at MGM for people who are doing Tom and Jerry shorts? They wanted to understand that.

They also wanted job security.

Costs change. Technologies change. World circumstances change.

…and at the time, in 1941, there was a war in Europe. You know, World War II had started in ’39. The U.S. hadn’t joined yet, but we were affected financially.

The Walt Disney Studio was earning only half of its revenue at that point because the whole European market was cut off.

So the studio was wondering: “Is the cost we’re spending on our technologies is really worth it?”

“Why are we paying airbrush artists if people will pay to see a Disney movie whether or not there’s airbrush paint?” for instance. So the whole airbrush department was laid off. (Which makes me a little sad to think about, because when you see some of the really cool effects animation in Fantasia, you’re thinking: “Oh wow, how did they do that with just paint on celluloid sheets?”)

[LAUGHTER]

…and so everyone was scrambling to find job security in this, not just the studio, but the whole field. Kind of like how people do now.

You have a history with a company (like The Writers Guild might), and you have done years, maybe a career’s worth, of good work, of loyal work, and you want to know that you’ll be able to, you know, retire one day and not live in poverty for your remaining years.

Chris: Yeah.

Jake: At the end of the day, they wanted the right to have union presence at the studio.

…something that every studio was having.

And, I hope it doesn’t spoil anything, but I do want to let listeners know that they won!

Like, it’s the happy ending.

They won!

They won the right to have a union.

Disney Vs. Disney:

Chris: It’s amazing how challenging it was. I think that’s something you never really hear about even as often as the Disney strike comes up it’s often this peripheral thing.

Jake: They were going down territory that no one had ever gone down before.

There had been a strike at Fleischer’s a couple years before (Fleischer’s being the studio that, you know, animated Popeye and Betty Boop, and that was over in New York). That strike was settled, but then the whole studio picked up and moved to Florida, for, like, union related reasons.

…and there were some other strikes in Hollywood prior to that.

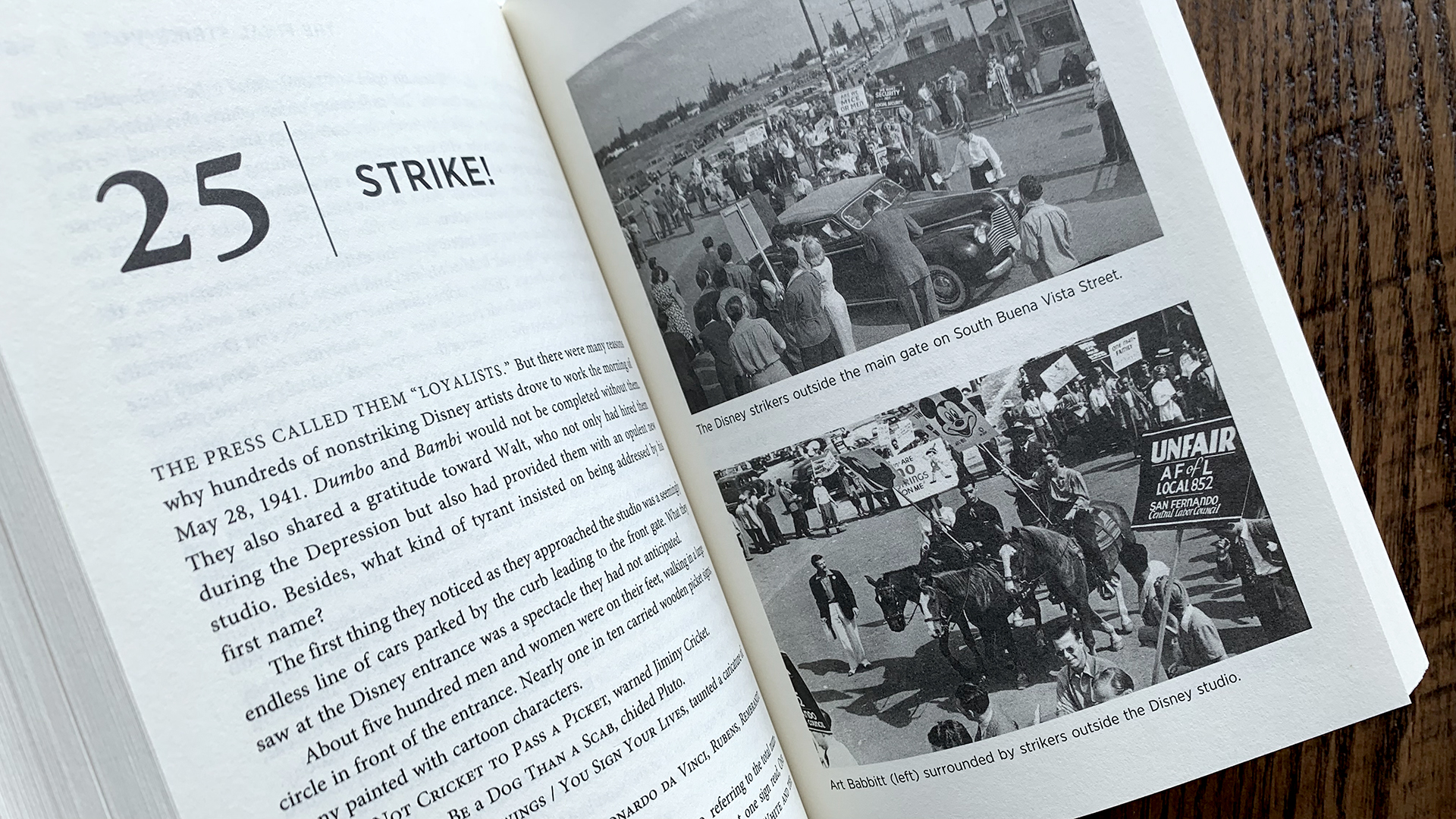

The animators wanted to make it different in a couple of ways. they wanted to make it safe; they didn’t want any injuries.

…and there weren’t any.

These folks went on the record, a couple of years later saying that it was the most peaceful strike they ever been a part of. (We’re talking about, people maybe bringing in hired goons to bludgeon strikers or really, like, physically intimidate them. So there wasn’t anything like that during the Disney strike.)

…but also, the Disney company was unique in that Walt tied his identity up with the company so tightly (as a means of, like, self promotion) that if you wanted to really get at the dragon’s belly, so to speak, you wanted to aim at his public image.

…and so you’re taking a lot of creative people, 330 creative people, making incredibly [LAUGHTER] attractive picket signs.

Chris: Right?

[LAUGHTER]

…and so creative!

[LAUGHTER]

Jake: So creative!

…and caricaturing Walt all over the place, showing the public that, “This man who is considered to be a friend of children everywhere and a hero to the creative community, he is making us unhappy and he’s bringing us out on the picket line.”

So, they knew how to really get Walt’s goat, basically, using his own strength against him. Walt’s strength had been tying his name up with the company.

It happened after the Oswald fiasco, right?

“No one can take your name away from you.”

…the way he felt Oswald was taken from him.

The company is his name.

Where else do we have a single person’s name in a movie studio?

Chris: Right, Jim Henson.

Jake: Right. But not at the time.

…and as far as I know, everyone who’s ever worked for The Jim Henson Company has been very happy.

Chris: Yeah, totally.

Art Babbitt – The Most Influential Disney Animator You’ve Never Heard Of:

Chris: When I first heard about your book, maybe my first thought was how challenging it would be to write a book with the strike, this kind of complicated historical event…

You know, it’s not the making of Snow White or something.

There’s politics involved, turns out, organized crime involved…

It could just be so esoteric and yet you, I thought, wisely, really made it a biography in many ways about Art Babbitt.

It’s about Walt, too, obviously, as you’ve just alluded to, but really the arc is this character of Art Babbitt.

What was his role in, and how did you arrive at that decision to focus on him and make it so biographical in a way?

Jake: It actually started out as a Babbitt biography.

My agent couldn’t sell it to any publishers. The publishers all came back with similar notes saying that, “It’s an important story, but no one’s going to buy the book. No one knows who Art Babbitt is.”

So I, I changed the scope of it into something that not just sells, but, I think, tells a more complete story. It’s the story, not of Art Babbitt, it’s the story of the strike.

…of the event.

…and who are the main players of the strike and how are they relevant to the strike?

That’s really what I wanted to write about. I didn’t want to do a “womb to tomb” book. That would have bored me as a writer. I really wanted to focus on how we get these two people about to punch each other’s lights out in the parking lot.

…how we get to that point from a point of almost friendship and a complete cooperation and sharing a single vision.

You’re right that it would have been esoteric had it just been about the blueprint of the strike.

That’s a good way to bore me as a reader.

I want a human story. I want a story about an underdog. I want a story that I can relate to being a person, and not just a person, but a creative person.

…and a person who would stand up for what he believes in to one degree or another.

And I think every one of us has that in us. I think every one of us has a tipping point where we will stand up defiantly against something that is challenging our values.

So that was Art Babbitt inside and out.

So much has been written about Walt Disney. I do not want to be redundant. I wanted to only tell the Walt stories that are relevant to the Disney strike.

There’s no shortage of biographical stuff about Walt and I was really forced by my editor to, winnow down like a hundred pages of the text. So…

Chris: Wow!

Jake: …but I thought 250 pages is kind of a reasonable length for a story about two men: Art Babbitt, Walt Disney.

How they were so aligned at a certain point…

…even to a point of almost reading each other’s minds.

Like, Walt was staying late at the studio, Babbitt would stay late at the studio. Babbitt would take work home with him. He was just so married to the idea of elevating the art form.

Not everyone at Disney was. The other people who came up in the ranks as Art Babbitt was (this is pre Nine Old Men), they kind of fell away.

…and, with a few exceptions, a lot of the people who trained Art Babbitt ended up becoming some very small potatoes in the animation industry.

…but Art ended up climbing the ranks with people who were there before him, like Norm Ferguson, and Freddie Moore.

…and then they kind of laid the groundwork for the animators who came after them.

…like, eight of The Nine Old Men.

All these young geniuses, people who were way too good for their age…

[LAUGHTER]

Like, there’s no reason why they should have had the skill that they had – all of them.

The thing about Frank Thomas and Ward Kimball and Milt Kahl, all those guys, is they all went to art school. They had graduated, like, a four year program from art school, and they brought that education up with them.

None of these other guys, Freddie or Norm Ferguson or Art Babbitt, went to art school.

But Babbitt was from a group of animators who were just expected to be able to know how to make sequential images and know how to work hard.

As I dug into Art Babbitt’s materials (through his widow’s permission) I could feel his presence, not in a ghost or a supernatural way, but just, like, I got to understand who he was and I began to identify with his personality traits.

I stand up for what I believe in, but he super-stands-up for what he believes in. I’m an animator, but he’s a super-animator. I’m an educator. He’s a super-educator. (I don’t want to get into how he basically created the field of animation education, but he did.)

…and the more I dug into his contribution to animation history, the more surprised I was as to how extensive it was. Like, he wasn’t just a lead animator. He wasn’t just a strike leader.

…but he, like, created the idea of method acting in animation, of the character analysis.

He created the idea of bringing art classes into animation studios and having the animators learn how to do figure drawing.

He was the one who pointed a live action camera at a movement specialist in order to inspire his animation.

…just to film someone doing a choreographed movement or any sort of thing like that, he was the first one.

He was so innovative.

All of these things are things that animation studios do all the time.

We kind of take it for granted.

I knew that his widow was so helpful and encouraging of me to finish this. She wanted her late husband’s legacy to live on because she noticed that his history was being brushed under the covers.

I was like, “I got I have to do this for this guy. If it were me I would want my legacy to go on.”

Reconstructing The Timeline Of The Disney Strike:

Jake: …so, I would just grab time wherever and whenever I would have my laptop.

…and I would sit in an airport lounge, waiting for my flight. I spent every minute of a flight a few times just going through notes and annotating a thousand-page courtroom document.

[LAUGHTER]

Chris: I was wondering.

I was wondering about that. Yeah.

Jake: It was great fun. Once you sort of tune your ear, it’s kind of like reading Shakespeare. If you read enough of it, you sort of understand the lingo.

…and I found that if I put it in chronological order it made a whole lot more sense. I could see the course of events. Nothing happens in a vacuum.

Every story about the strike prior to this book ends up being like: Workers weren’t happy. Boom, they went out on strike.

…but it really started in 1938 when the first seeds were sown. And, little by little, people were getting more and more unhappy and laying the groundwork for what would become a strike.

So knowing that it didn’t happen in a vacuum, I really had to…

I used my iCal, my, my calendar program on my laptop. I went back to 1938, 1939 and I put in these events on the dates that they happened.

Chris: That’s awesome.

Jake: It was a great tool. And that became just a really convenient way to see, “Oh, this happened. Then that happened. Then that happened.”

It sort of revealed itself to me.

…and I became hungry for more.

I never collected baseball cards, but kind of like if I was missing a card… “What happened in between this date and that date? I really have to find out.”

It became like I was a completionist who was obsessed with figuring out how we got from A to B. “Oh, I understand the event over in C, but how did we get there?”

I also knew that a lot of these things were really big ideas and I wanted to organize my notes into sort of cohesive narrative style, kind of, presentations or articles.

So I created a blog called The Babbit Blog and that became my source for organizing my notes. It just was something to help me out.

…and that got a lot of people’s attention, and a lot of other people who are Disney history enthusiasts reached out to me.

Even some people who are part of the story reached out to me. People who helped me complete the picture who I never thought I would ever be meeting or talking to…

That blog was a great starting point. I just kind of did it obsessively.

It was great fun. The reason why I couldn’t stop, I think, is because I really saw Art Babbitt as a three-dimensional person and that, in no small part, had to do with his amazing widow named Barbara Babbitt who just let me into their home and dig through all of their stuff.

It was so special and I’m so grateful for her. Her daughter says that they’re grateful for me. So we’re just in this mutual gratitude loop.

Would The Disney Strike Have Happened Without Art Babbitt?

Chris: Do you think there would’ve been a strike without Art Babbitt?

Jake: He is letting his feelings get in the way of his politics all throughout that period.

It really came to a head when he was feeling like he was a stool pigeon – that he was used by the company.

He didn’t like being played. And he was feeling like he was being played.

Basically, he realizes that the studio only allowed him to create a company-led social organization (that he took to be a union) to strengthen the company. Not to strengthen the workers.

…and Babbitt has this realization. He’s like, “Oh my god I’ve been played. Screw these guys. And not only that, but screw the individuals. Screw Walt Disney. Screw Roy Disney. Screw their vice president Gunther Lessing.”

He knows these guys personally and he’s saying, “I’m going to make their lives difficult. Not because I believe only in my union beliefs,” which he did, “but also because they played me. Now I’m going to hurt them.”

So he joins the independent union, The Screen Cartoonists Guild, and he immediately starts a boycott. He starts a nationwide boycott of Disney products and Disney films, trying to get people all over the country, all of the unions that collaborated with The Screen Cartoonists Guild on the East Coast and West Coast, to stop patronizing theaters showing Disney films.

I mean, that’s kind of a vicious move to make during a war crisis and depression when every penny counts, but he just, kind of, wanted to stick it to them.

Babbitt’s role in starting the strike, for a lot of people, he was kind of the fire under their butts. And he was incredibly undiplomatic and he was taking everything personally.

Chris: Right.

Loyalty Above Creativity?

Jake: And I can say the very same thing about Walt.

Chris: Yeah. Exactly.

Jake: Walt was taking it personally.

Walt valued loyalty above everything.

Loyalty.

If you watch the movie Snow White, to this day, you can see the title card right after the name of the movie, it’s a note from Walt Disney thanking his staff for their quote “loyalty and creative endeavor.”

Yeah.

So, of the two most valuable traits he finds in his employees, he names “loyalty” as one of them.

…and that’s the one he puts in front of “creative endeavor.”

So, I mean, I put stuff in the book about Walt’s background and why he feels like loyalty is his most precious commodity. What happened to him in his youth, what happened to him in his early adulthood, why he has been triggered to value loyalty above all else, and why it means so much to him that Babbitt became a Benedict Arnold to Walt.

Chris: It’s amazing.

We’re All Products Of Our Influences:

Chris: Once we start getting into the more biographical details of Walt and Art Babbitt specifically, there’s stuff in there where I was kind of like, “Okay, the book has been so focused up till now, this has to connect to the strike somehow, but I don’t know how it’s going to,” like, “I have no idea how this is going to connect.”

There are payoffs established early on that don’t pay off till much, much later in the book and even when you think that something might be kind of a tangent, it’s not. It connects.

Jake: We’re all the products of our influences and I was trying to really get into a psychological profile of Walt and Art.

…not to sound too hoity toity.

…but Walt especially, he…

Even Roy would say that Walt was able to retain memories from his early childhood like no one else he knew.

…and that’s probably why he had the gift of creating children’s entertainment that connected to all ages.

No matter how old Walt got, he was able to tap into his childhood experiences.

…and he would tell stories later on in life about things that happened to him when he was five or six.

Jake: So I wanted to sort of understand how these things influenced him and how these things influenced Art.

They had so many things in common, like, they both had a Midwest upbringing. They both were paper boys. They both sort of had to work harder than other people in their age group just to get by.

In Walt’s case, he had a very authoritarian dad and in Babbitt’s case, his dad was severely injured and Babbitt was the eldest child. So he sort of had to become the breadwinner.

How Walt Disney Is Like Michael Scott From “The Office”:

Chris: As I’ve learned about the strike many times over the years, I was always a little confused about how Walt seems so shocked [LAUGHTER], you know, that the crew went on strike. I’ve always been kind of baffled by that.

…and in reading your book I was thinking about how Walt kind of seems a little bit like Michael Scott from The Office [LAUGHTER] where, he kind of thinks his coworkers are also his family, and that can lead to problems…

That’s not to say that one can’t develop really rich, meaningful relationships with colleagues, but just because you see them every day, you can’t assume.

…and it seemed like Walt assumed.

What is your opinion on that?

Jake: That’s a great comparison. I never [LAUGHTER] put that comparison on Walt before.

I totally get it. I totally get it.

I think, in a lot of ways he is very much like Michael Scott.

…where he values employee rapport and he wants to make his employees happy.

…and he was making a lot of them happy.

Not all of them went out on strike.

Just the very slight majority went out on strike.

So there was almost half who stayed inside and those are the people who were like: “This is great! I get to work on some great projects. We get a brand new campus in Burbank instead of those slipshod buildings over on Hyperion Avenue.”

“We have all of these benefits like a coffee shop or a garage that’ll service your car or, for the inkers and painters, we have tea time on the roof or we have an athletic gym on the top floor for people earning a hundred dollars a week or more.”

A lot of people felt like this was great and a lot of people felt, “No, we have these fancy new buildings, but I would much rather have the money for my family than fancy new buildings…”

It’s so interesting that people who worked on Snow White, most of them were young folks in their twenties and hadn’t yet begun building families or paying mortgages on homes…

… but in just a few years, like five years after that, even three years after that people are starting to grow up a little bit or reach the next stage In their lives and they’re like, “I want to invest in a family and I want to invest in kids.”

Jake: People are getting to the next stage in their lives and being in a shiny new campus isn’t enough for them.

When Disney History Repeats Itself:

Chris: That literally happened to me.

We got a new building – big, beautiful building.

It was massive and had all the state-of-the-art conveniences.

Basically, when you get a bonus check, depending on how much you worked on the movie (how long or what your role was) you would, you know, get proportionally more of a bonus.

The year before the new building. I got a bonus check for a movie I did not work on because I was just employed at the studio by the time the bonus checks came around. My bonus check for the movie I did not work on was maybe three times, maybe more, of what I got for my bonus check for a movie I did work on after the new building.

I went to someone who was above my pay grade and I said, “It just seems like we’re the ones paying for this building.”

I was not pleased with the reaction.

Yeah, I’ll leave it at that, but it was not a pleasant, uh, conversation.

Jake: Wow.

It’s like a copy-and-paste of what happened at Disney.

They were earning really generous bonuses.

There was this profit sharing program that went into effect in the mid 30s. People were getting paid like the equivalent of several months’ worth of salary in a bonus check.

…and Babbit was getting a lot. He was turning in very good work and Walt was recognizing it. So he was getting these really sizable bonus checks.

…and then after Snow White, Walt started taking all the revenue from Snow White and investing it in this new series of buildings.

The bonuses stopped.

…and people were like, “Where are the bonuses?”

What you just said must’ve been going through all their heads verbatim.

“Feels like we’re paying for this new building.”

Chris: He seems personally offended like, “Look at all these things I do for you and you’re upset. I don’t get it.”

…and I’m kind of like, “Walt! Read the room.”

You know?

[LAUGHTER]

Read the room like five years ago!

Jake: It’s like Michael Scott coming in with a bag of ice cream bars and saying, “Here’s the surprise!”

[LAUGHTER]

Chris: Right? [LAUGHTER] Yeah, that’s right. Oh, goodness gracious.

Jake: I think, as artists, we want to be appreciated.

We want people to know that our work matters.

Then show us, in one way or another, that our work matters.

…and I think a lot of these artists who went on strike at The Disney Studio (if I were to just make an assumption) I think they were feeling not just unappreciated but maybe like they didn’t matter enough to the boss.

You Can’t Fire “Family”:

Chris: I remember when I was doing some training as an employee, and I remember them talking about how, you know, “We’re a big family.”

That’s one thing that I do love about Disney.

It’s that it really does have a warm, familial feeling.

…and it’s a fun place to work, so long as you’re actually employed there.

There’s the rub.

I’m going, “Yeah, ‘family,’ until they buy a new building and the bonus checks disappear,” or whatever, “and then you’re not family anymore.”

Right?

It’s like, “Well I thought we were family.”

You know, sometimes I’m a statistic and sometimes I’m “family.”

You can’t have it both ways.

It’s one or the other.

Jake: I think if a person can be laid off from a group of people, then it’s not a family.

Chris: Yeah. [LAUGHTER] I think that’s accurate.

Jake: My parents aren’t going to fire me.

“We have a replacement son coming in.”

Chris: Right, yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

“He’s cheaper.”

Jake: “He’s cheaper and he complains less.”

Chris: Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

Jake: “He calls home more often.”

Chris: Yeah, there you go.

It seems like there were several factors that led to the strike that kind of had to combine.

…and some of them were obvious.

…like low pay, for example.

But then there were other factors like Walt’s perfectionism.

Though it might not be the most direct cause-and-effect relationship, it certainly seems related.

I mean, that was, I think, the central tension for Walt as a businessman, right?

…and he even complained about that.

‘The problem is they always have to make money. I just wish money wasn’t a thing.’

My point is that Walt’s perfectionism really seemed to come at just about any cost…

…to a certain point. After Saludos Amigos they were trying to, kind of, find ways mitigate, but, it took a long time for him to get there.

…to this point where, you know, he was willing to do anything he would view as a compromise artistically.

…and that, of course, led to the strike (or at least I think it leads to the strike) because it seems like the consequences of that are longer hours.

…or, like you were saying, the work getting thrown out, and then maybe somebody doesn’t feel like their work was acknowledged because now it’s in the bin.

What do you think about that perfectionism angle?

…and then do you think there are any other factors that led to the strike that might not be as intuitive?

They Admired Walt’s Perfectionism (For A While):

Jake: I think that perfectionism was evident during the 30s when they were still working on shorts.

For one thing, Walt was the only animation studio head who had a story team. No one else had a story team, a team of writers.

He was the only animation studio to have pencil tests. No one had a bunch of Moviolas. Most studios had one Moviola for the editor to use for, final editing.

So, Walt, I think, during the 30s (at least according to the letters of people like Art Babbitt that I’ve read from that time), they admired Walt’s perfectionism, even if it meant longer hours.

…because, at the time, they didn’t have anything else except the desire to create something marvelous.

…and they could put in longer hours.

They could put in something for a common vision.

They wanted to excel at their craft.

How Walt Disney Supported His Artists:

Jake: Ward Kimball animated an entire soup eating scene from Snow White. Walt knew that it was hurting Ward, so he said “Okay, Ward, I’m going to make it up to you. I’m going to give you a major character for the next picture.”

…and that character was Jiminy Cricket.

So that was Walt understanding what it’s like for an animator to work on animation only for it to end up in the garbage bin.

For Pinocchio, they kind of started, maybe, prematurely, because there were a lot of story problems that required everyone to just stop the presses.

…pull a halt for a matter of months while Walt gathered himself back up together.

He had to, sort of, rewrite the story, take out this, emphasize that, make more Jiminy Cricket, take out some characters, take out a birthday party…

J.B. Kaufman wrote a book on Pinocchio that talks about how tumultuous this production was, at least in the first half, when people are like, “Oh my god. I did all this work. I designed all these characters and now they’re not going to exist anymore.”

But what Walt did was, even though animators weren’t working on anything.

Like he’s telling them to, “Just keep busy. We’ll figure out how to use you. Just keep busy. Teach the other guys what you know. Keep working on your skill. Keep designing.”

So even though there were slow periods and he could have laid them off temporarily (save some money there), he kept them on.

…which was something that, at least in Art Babbitt’s self-stated letters and courtroom testimony, kind of, surprised him.

…that he was kept on during these really slow periods just because Walt didn’t want to lose him.

…and so when it was time to pick up production, “Ah! I know what the story’s gonna look like. We hammered out all the kinks. We’re going to get this going in such and such a way…”

Babbitt’s like: “Okay, I have a redesign for Geppetto, let’s get started.”

…and, in that way, I think everyone did feel like Walt’s perfectionism paid off.

These movies are super expensive to make.

…and, if not for the fact that they lost money making them, I think it wouldn’t have been a problem.

I actually think that the war in Europe is a big cause for why a person might think Walt’s perfectionism was a barrier towards workers being happy.

…because there was a limitation of resources.

The war created this depletion of this revenue stream.

Without this depletion, Walt could have just spent more money and made more money.

Chris: It’s this combination of things.

You know, it was a very specific point in time and it’s a really fascinating thin slice of history in general, in that way.

Jake: So many things coming to a head all at the same time.

The Emotional Ending:

Jake: If you wouldn’t mind if I turn the tables a little bit?

You’re asking such amazing questions and it tells me how deeply you read into the story and how much it meant to you. I’d really (and I think your listeners would really like to know) like, what was your experience reading the story?

Chris: Brian McDonald, my friend and mentor, (He’s worked on all kinds of amazing projects. He’s a story consultant at Pixar. He worked on God Of War 2018.) I mean, he’s an amazing, story person.

He said in his book Invisible Ink that a focused story puts the audience at ease because they have the sense that the storyteller is in control…

…and I had that sense very early on.

This is a hard topic to write about because it could just so easily meander all over the place.

It could be really unwieldy, esoteric, etc.

…and so it was, even by contrast, that much more amazing.

I was hooked pretty early on, but then I don’t think I was prepared with how emotional it would be.

Basically, from the point where the strike ends…

From about that moment on I was just really gripped, emotionally, and then literally moved to tears. There were a couple moments that were really emotional but then there was one point where I just…

It really got me near the end.

I didn’t see that coming.

Jake: If I can guess, broadly, about what you’re referring to, it’s the fact that the strike was so consequential to all these guys, even into their old, old age.

It was still a defining moment in their lives.

…and that the relationships that they had with people who were on the opposite side of this battle.

…or, even with the company, their relationship to The Disney Company and to their legacy of having worked on these wonderful pictures even after they couldn’t go back.

…that that was something that just stayed with them for forty, forty-five years.

Well, ’till death, really.

Chris: Yeah.

Jake: …and that it was something that they really sought to make peace with.

…and it’s not just Babbitt who certainly was embittered by it, but so many others had these bitter feelings about it.

…and there are folks who would go on the record in their old age, basically, waving the flag as if they were still on strike, talking trash about Disney and all those emotions would get stirred up again.

I would have loved to have seen just some sort of handshaking and just letting bygones be bygones, but both sides were taking it personally.

…and I don’t think it needed to be that.

Chris: Yeah, It was costly. It was so costly.

…and I think you really did an amazing job at conveying how painful it was for the people who went on strike and how brave, really, they had to be in order to take the stand that they did.

Jake: Yeah, a hundred percent.

Did Walt Learn Anything From The Strike?

Chris: Do you think Walt learned his lesson?

Jake: No. I don’t. I really don’t.

Walt kept Art’s name out of his mouth for the rest of his life. Never mentioned his name again.

You can actually listen to Walt’s interview. He does an audio interview. You can hear it at the beginning of the very, very wonderful documentary by Ted Thomas, Walt and El Grupo.

Chris: Oh yeah, it’s great.

Jake: Fifteen years after the strike, Walt is talking about the events of the strike with such emotion and talking about how hurt he is about having his name smeared.

And his daughter, Diane (I think, in the same documentary) says that besides his mother’s tragic death, the strike is the one thing that really put her father in an upset place that he was never able to recover for the rest of his life.

…emotionally.

I think Walt was wounded.

Clearly, whenever he brought it up, it was still fresh for him.

Was Walt Anti-Union?

Jake: …but I think the reason why he thought that he was given the unfair treatment in the strike resolution was because he was given such a biased, echo-chambery influence from his vice president, Gunther Lessing.

…and Gunther Lessing isn’t really a name that people who talk about, you know, Disney history often bring up.

One reason is because his role was significantly diminished in the company after the strike because Roy and the other members of the managerial staff felt like Lessing mismanaged the situation tremendously.

…but Lessing had, basically, allocated himself to be the labor liaison.

How can you have an independent labor negotiator who’s working on the company’s dime?

…and he was doing all these tactics like trying to bring all the employees into meetings that were anti-union.

…just a series of really nasty tactics.

But in addition to that, he was ( and the strikers felt this too), he was overloading Walt with, kind of, conspiracy information, making Walt think that all unions are communism-led.

…when it just wasn’t the case.

I have evidence that one member of the strike committee (the secretary of the strike committee) had joined the Communist Party when he was in Russia working in a theater arts program. But no one else was a member of the Communist Party.

…and, just like today (you can turn on one TV channel or another) there were right-wing newspapers and left-wing newspapers and they would publish articles, columns, periodicals that were kind of like enforcing their narrative.

People meeting close to the middle ended up having a huge divide because of these echo chambers.

…and in no small part due to Gunther Lessing, the vice president of The Disney Company, pushing Walt more and more into this idea that, “These are communists and they have to be stopped and they’re destroying our country.”

Chris: You think Walt just bought it all and rode that wave?

Jake: I do.

Gunther Lessing knew how to play Walt. He knew how to make Walt feel like his security was threatened.

Walt knew that he was not great at everything, and he wanted to free up his own mind to sort of imagine and do some creative play so he said, ‘Roy, you manage the business side. I don’t care where the money comes from. You just find it.’

‘…and, Gunther Lessing, you just manage the law stuff. You’re my chief lawyer and my vice president. Handle things from that angle.’

It was just easier for Walt just to delegate and trust that these people were the best in the business and that they were out for his best interest.

…and in the end, Lessing, I think, was out to sort of protect himself and reinforce Walt’s already-held beliefs, which just became more and more biased against unions as Lessing continued to play him.

Learn More At TheDisneyRevolt.com:

Chris: Well, there is a cost to standing up for your rights as a worker and the rights of your colleagues as a worker. There’s a cost and sometimes it, uh, is significant.

…and, it, can really take its toll.

…and, yet, I think there’s some really emboldening insight that can come from your book, Jake, and I really appreciate you writing it and having the vision and the patience to navigate that project.

Chris: Is there anything else that we didn’t get to that you’d like to cover?

Jake: I just want to plug the website because I put up so much of my research on the website for free for anyone to just look at and enjoy and be inspired by.

It’s at TheDisneyRevolt.com

You can find tons of my original research all in one place. There’s a timeline there. There’s a “who’s who?” There are a bunch of original materials like handbills and memos that they were reading at the time.

…which was incredibly helpful to get into the mind of what the strikers were experiencing on a day-to-day basis.

There’s also a link to the audiobook which you can listen to for free, the first 30 minutes thereof.

Stand With Animation:

The Animation Guild (which holds the major U.S. studios accountable) is currently fighting for “fair wages, job security, and common-sense guardrails around Generative AI use.”

You can learn more and sign the “Stand With Animation” petition at this link.

In Our Next Episode:

Interacting with COLOR!

Every Successful Art Career Is A Collaboration:

Get clear, relevant feedback on your work and personalized career guidance in our mentorship: The Clockwork Heart.

Never Miss An Episode:

Subscribe to this podcast on any of the major platforms (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, YouTube) and join our email list for notifications about future episodes, courses, and mentorship opportunities.

It’s 100% free and we will always respect your privacy.

Credits:

I’m your host, Chris Oatley, and our production coordinator is Mari Gonzalez Curia. Our music is by The Bright Sigh (which is me) and this show is made possible by The Magic Box Academy.