In this episode of You’re A Better Artist Than You Think:

The Jim Henson Company Archives director and historian Karen Falk offers insights into Jim’s creative process, his collaborative style of leadership, the evolution of Miss Piggy and more…

We encourage you to check out the video version of this episode (embedded below) where we feature images from the new edition of Karen’s book titled Jim Henson’s Imagination Illustrated as well as photos and video clips from our visits to various Henson exhibits.

How To Listen:

Listen via the YouTube player below or subscribe to the audio podcast via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, Email and most other podcasting platforms…

[UP NEXT: You’re A Better Artist Than You Think season three begins Spring 2025!]

Interview Transcript:

Chris: I’ve been a fan of your work for well, really, since the Red Book Twitter account started.

I’ve been to a bunch of the exhibits…

Jim is probably the most important artist in my entire life.

…so it’s really special to be able to talk to you today.

Karen: I’m thrilled.

We have such amazing fans.

Chris: I have so much that I want to discuss and, of course, we’re going to focus on the book.

…and I thought we could just start there…

Jim Henson’s Imagination Illustrated: Second Edition

Chris: There’s a second edition of the book out.

For the listeners who don’t know anything about it, could you give us a little context about the original version?

…and what’s in the new edition?

Karen: Sure!

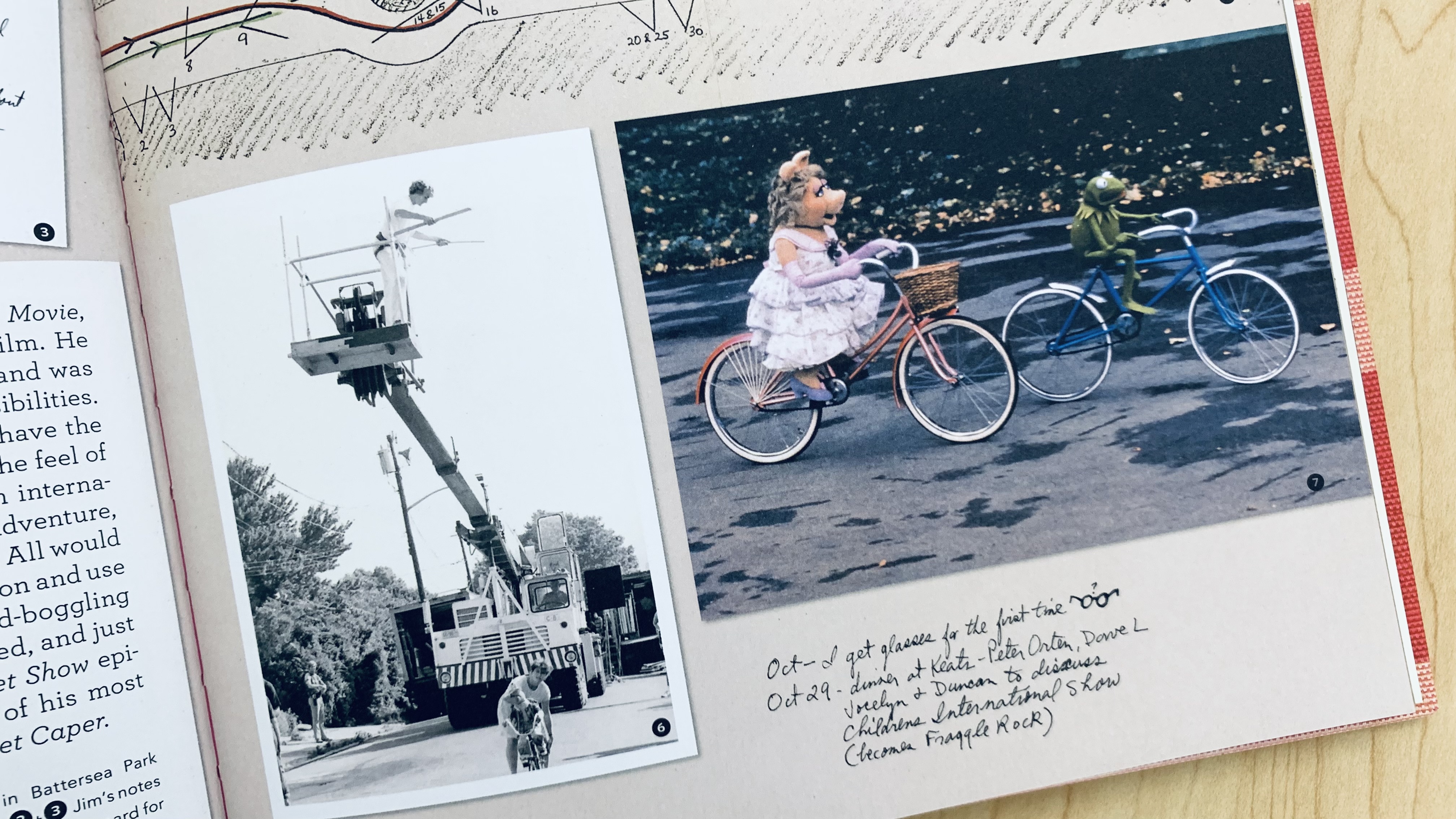

The original version was a direct result of the blog that I wrote, the Jim’s Red Book blog.

I had compiled a lot of information and materials and it seemed obvious that we should turn it into a book.

So we did. We worked with Chronicle Books in San Francisco.

It was an interesting process for me because on the web you have the ability to use as many words as you want. There’s (sort of) unlimited space, and so I was able to write quite a bit.

For the book, we wanted to put as many images as possible in each spread. There’s so much material in the archives that I was eager to share, so we really had to limit the text portion.

There was a lot of editing that happened to the blog posts to get them down to just the essence of the idea. Then we let the images speak for themselves, which was great.

The goal of the book, for me, was to really share so much of what was in the archives and get it out there.

When it went out of print, I was disappointed because I felt like there are still people out there that would be interested in this.

I feel so privileged that we were able to work with Ron Howard‘s team on his documentary and provide all of our archives to his team for Jim Henson: Idea Man.

His making that film then allowed us to say to a different publisher, “Can we get this book back out? We think there are going to be people who are going to want to know more about Jim Henson when this film comes out and this book is a nice companion.”

Ron told me he liked the book and used it, obviously, as a jumping off point when he was just starting his research.

And so he was very kind to offer to write a foreword for the new edition. That’s the big change in this version. It has Ron’s perspective on Jim at the beginning of the book.

I feel so fortunate that all of that came together so that we could get this book back out and, once again, have this material available to fans and artists and people like you!

More Than Muppets

Chris: The pages are like a collage (for those who haven’t seen the book).

I’m so glad that all the people that I’ve told about these exhibits get to experience something kind of like it in the book.

Could you tell us a little bit more about what”s in there?

There’s every imaginable kind of ephemera, you know?

It’s not just Muppets, right? There’s a lot more to it than that…

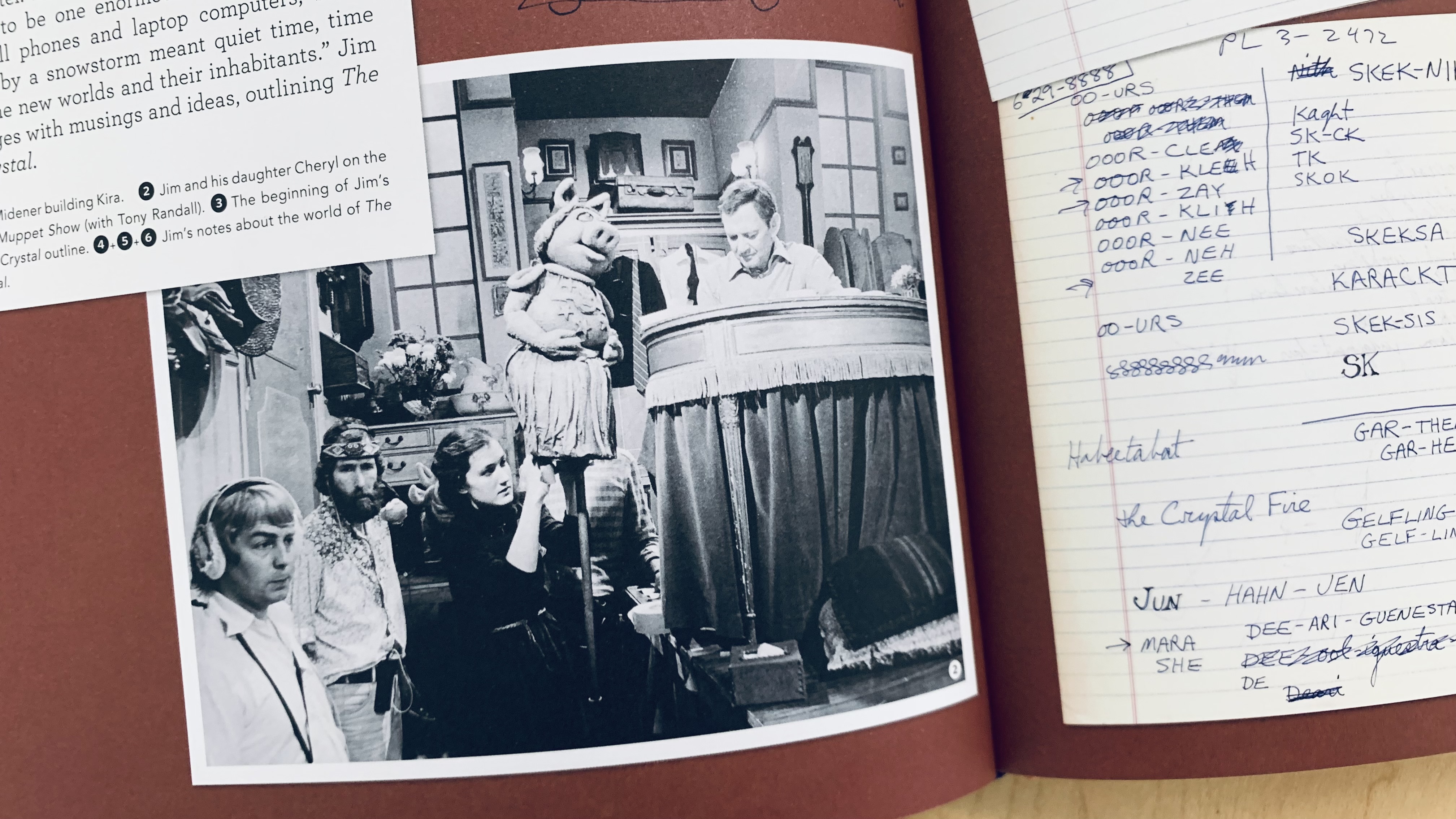

Karen: Well, the skeleton of the book is Jim’s journal that he kept, Jim’s “Red Book.”

That was something that he kept throughout his career, listing the highlights.

And that includes every aspect of his work. His very early work on television in the 1950s and 60s, his commercial work leading up to Sesame Street (I mean, he was on TV for fifteen years before Sesame Street and the Muppets) but also his experimental work, the fantasy films, any kind of collaborations that he did with other people, other creators, family events, things like that…

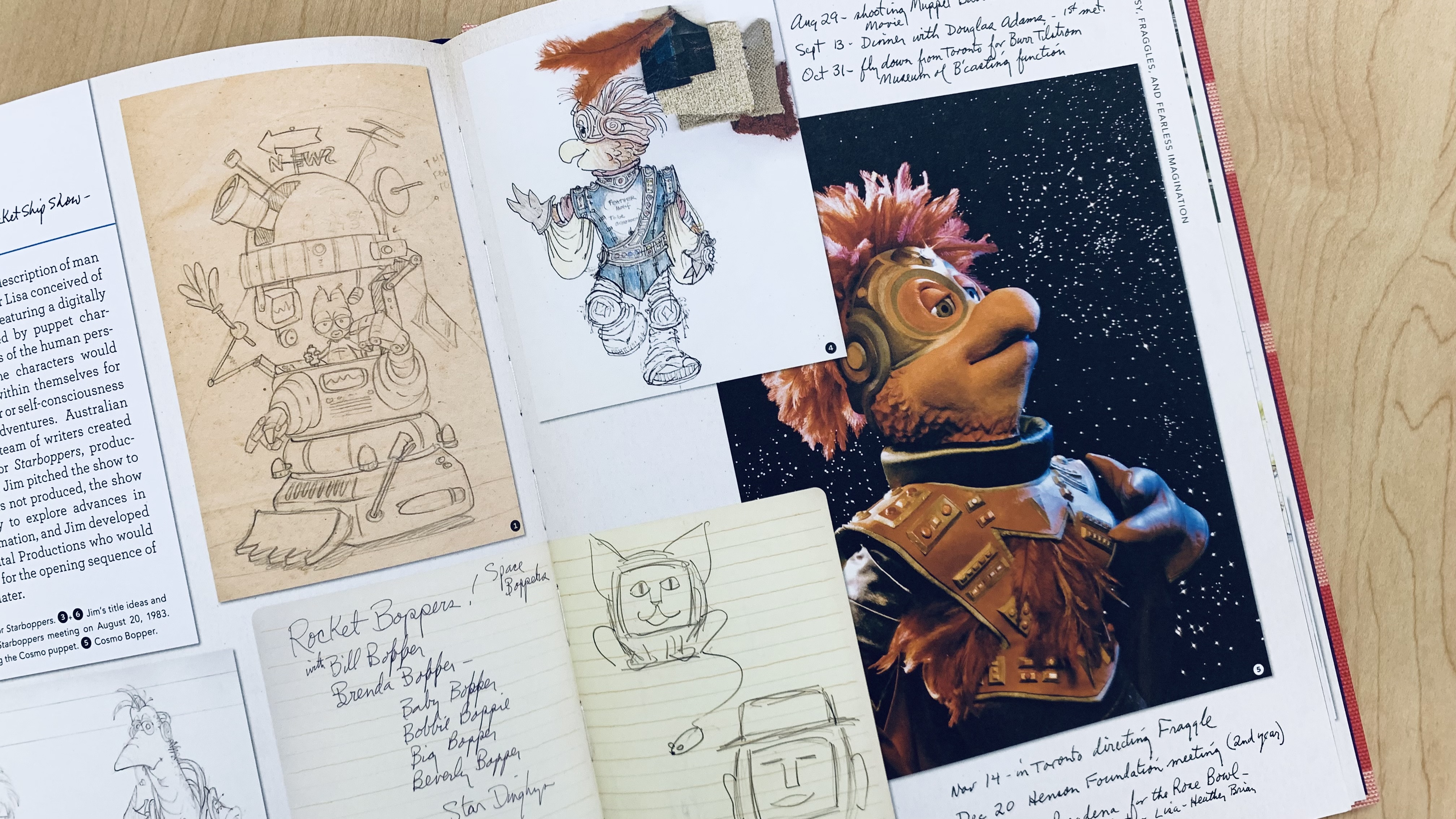

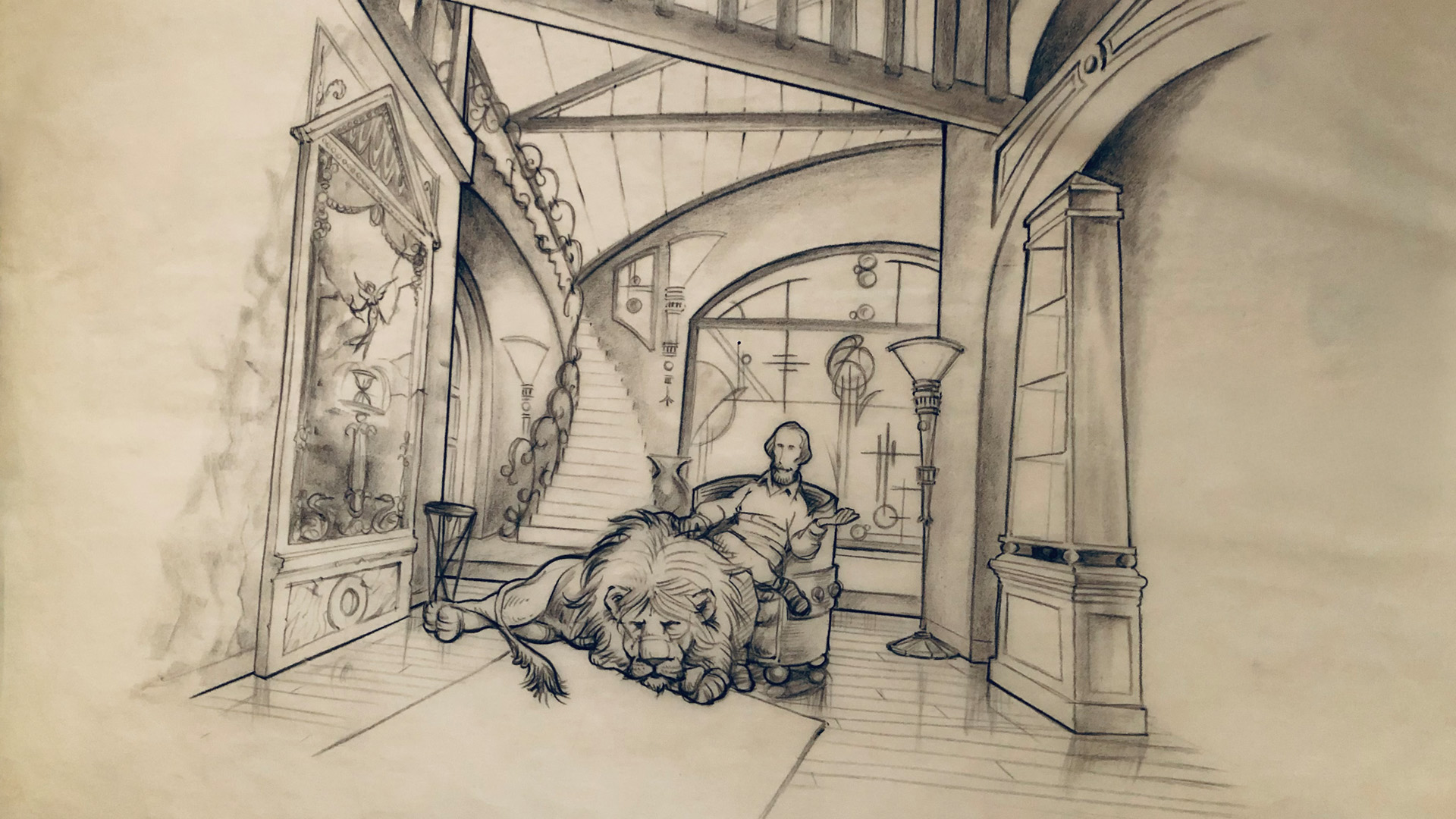

And then, of course, things that didn’t happen. We have images and sketches from projects that Jim experimented with. For example, Starboppers, which was from the early eighties. That was a great project that fascinated Jim.

He was wanting to do something where he used digital backgrounds and put his puppet characters within a digital environment. That was going to be Starboppers.

Jim worked with some great artists, including Ron Mueck on that (who’s a wonderful contemporary artist who’s now in major museums) and never sold the project, but it moved his creative vision forward.

I was hoping to express in the book how Jim really built on his ideas.

You see drawings or sketches or notes early on in his career and then that idea gets reformatted and used later in his career in a different way.

Big Bird, for example…

In the early sixties, Jim drew a design for a bird very similar to Big Bird, with the same puppeteering method and everything. It was going to be for a Stouffer’s frozen food commercial, which is fun, but it didn’t happen. He tucked the drawing away in his files (which, of course, eventually ended up in our archives).

…and then you see, about five or six years later, his design for Big Bird, and it’s very similar.

He never wasted a good idea.

It was fun to be able to put those things in the book and not hit the reader over the head, but allow them to make those discoveries themselves as they get to something say, “Hey, didn’t I see something back there that was similar?”

Chris: Yeah. It’s fascinating.

Jim’s Personal Touch

Chris: You get so much biographical essence from the raw honesty of Jim’s art…

There are so many of his sketches and doodles and jotted-down ideas…

And his handwriting is all over the book and so there’s that literally personal touch there…

I mean, that’s true for so much of his work, but his spirit is really visceral throughout the book.

Karen: Well, That’s what I wanted to give readers the chance to experience.

I came into the archives thirty-two years ago so I’ve had the leisure, first of all, to really be able to think about all this material and think about it over a long period of time and really study it and think about the way it fits together.

I’ve been able to really connect with these very personal objects of Jim’s, whether it’s his journals, his little doodles, his memos, things he was doing with his family, family photography…

I wanted to open up those drawers and cabinets to people who were interested in Jim and young artists who were inspired by Jim to be able to experience that a little bit.

Chris: Mission accomplished!

Jim’s Fearlessness

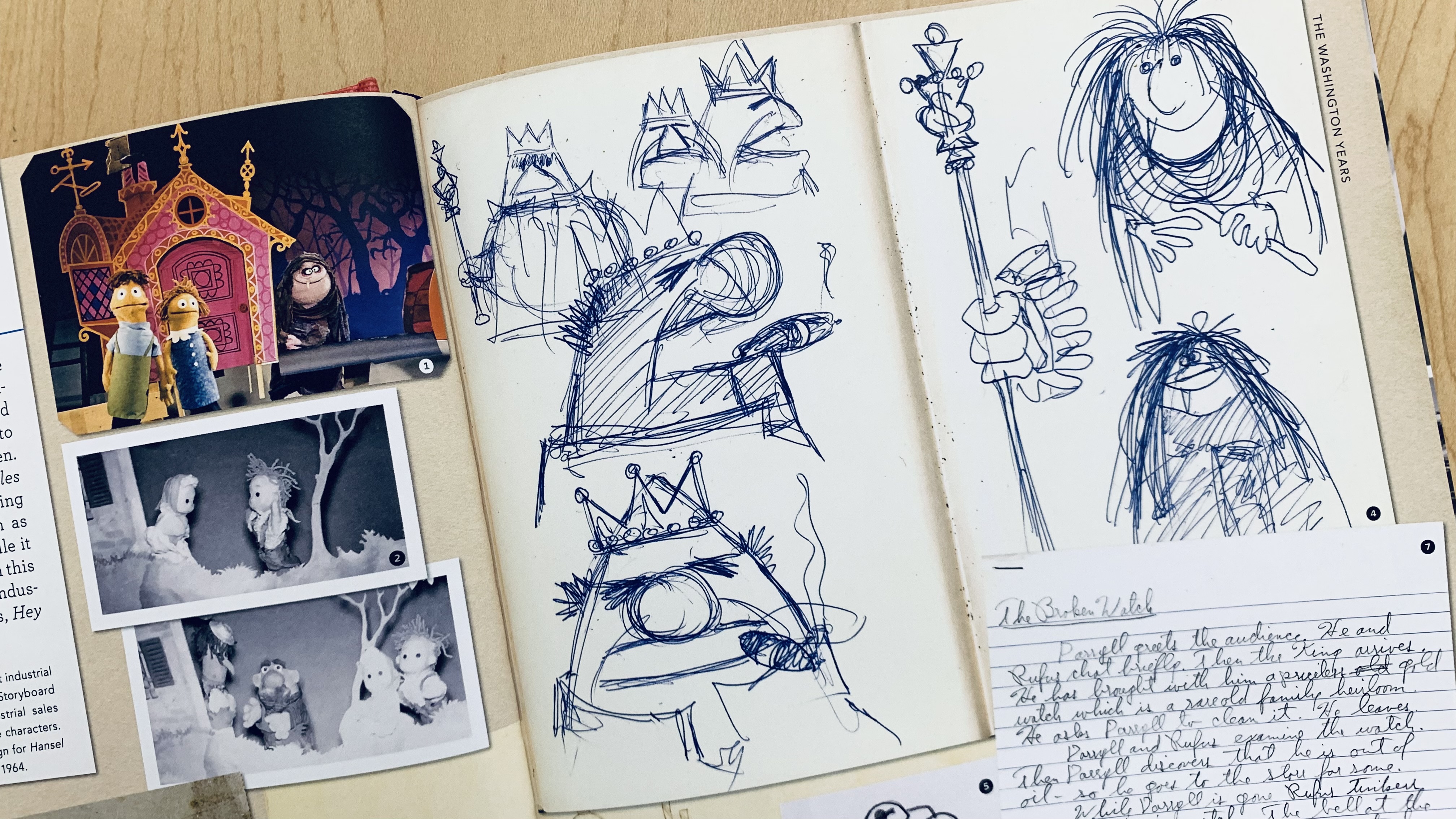

Chris: Can we talk about the reckless abandon of Jim’s drawing?

He is so unfiltered and unedited and many of his sketches are almost naive by design…

…like that’s the desired effect.

They don’t look like a child drew them, but there is a looseness and a wobble to the drawings that is just so unique and specific.

Nobody draws like Jim Henson.

That’s not a question, but…

[LAUGHTER]

…I’ll just throw that out there and just see what your take is on that aesthetic.

Karen: Well, I think that, for Jim, it was visual note taking.

I think a lot of his artwork was very much just jotting down his ideas in a visual way, a graphic way…

…as opposed to a textual way.

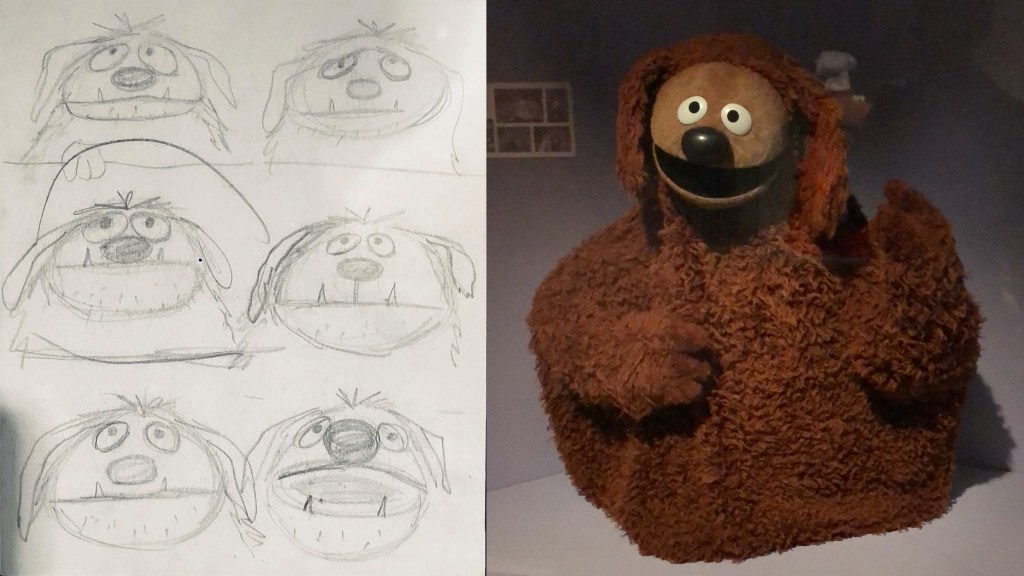

We always say that, when he hired Don Sahlin to start building puppets in 1962, Don was the one who could really read Jim’s drawings and immediately grasp the essence of the idea of the character, what Jim was going for, and then produce a character that looked surprisingly like Jim’s little sketch.

Don understood whatever that essence was that Jim was going for when he made the character.

Jim Henson: Character Designer

Chris: It’s amazing, something you said there about how well the actual physical Muppets are translated from Jim’s drawings.

There’s an elemental quality, of course, to the Muppets.

It’s the most pure character design, really, in so many ways…

And I teach character design and many of my students have a Disney framework, right?

But I start with the Muppets, usually, because if you can get appeal with five shapes, you’ve done the hardest part of the character design.

But then to not just make that unique and iconic and recognizable, but to translate it into three dimensions?

That’s bonkers.

From 2D to 3D

Karen: I think that’s the big challenge – taking his drawings and turning them into three dimensions.

…which, obviously, the artists in the workshop here are so skilled at.

When Jim started, his original characters were not started on paper. He just built puppets. They weren’t based on drawings and he built them and Jane Henson built them. They built them together.

And as that first part of his career doing the Sam and Friends characters progressed, they got a little bit more ambitious.

There’s a photo essay from 1959 of them building a Theodore who was also called Chicken Liver from Sam And Friends.

We have Jim sketches for him and Jim sketched him from different vantage points. I think he was trying to get that sense of the three dimensions on paper.

He had never done that, really, with his characters before. He hadn’t sketched them before he built them.

And then we have pictures of him sculpting a head based on his drawings, which was a way to do drawing in three dimensions in effect (and then, eventually, they finished the character).

A More Professional Finish

And it was not that long after that, that he met Don Sahlin and hired him to start building.

I think he wanted a more professional finish to his puppets.

Jane Henson always said that, initially, they wanted their characters to look handmade.

They wanted them to look crafty, to look like they were coming from the rag bag, and that it was okay if it looked that way.

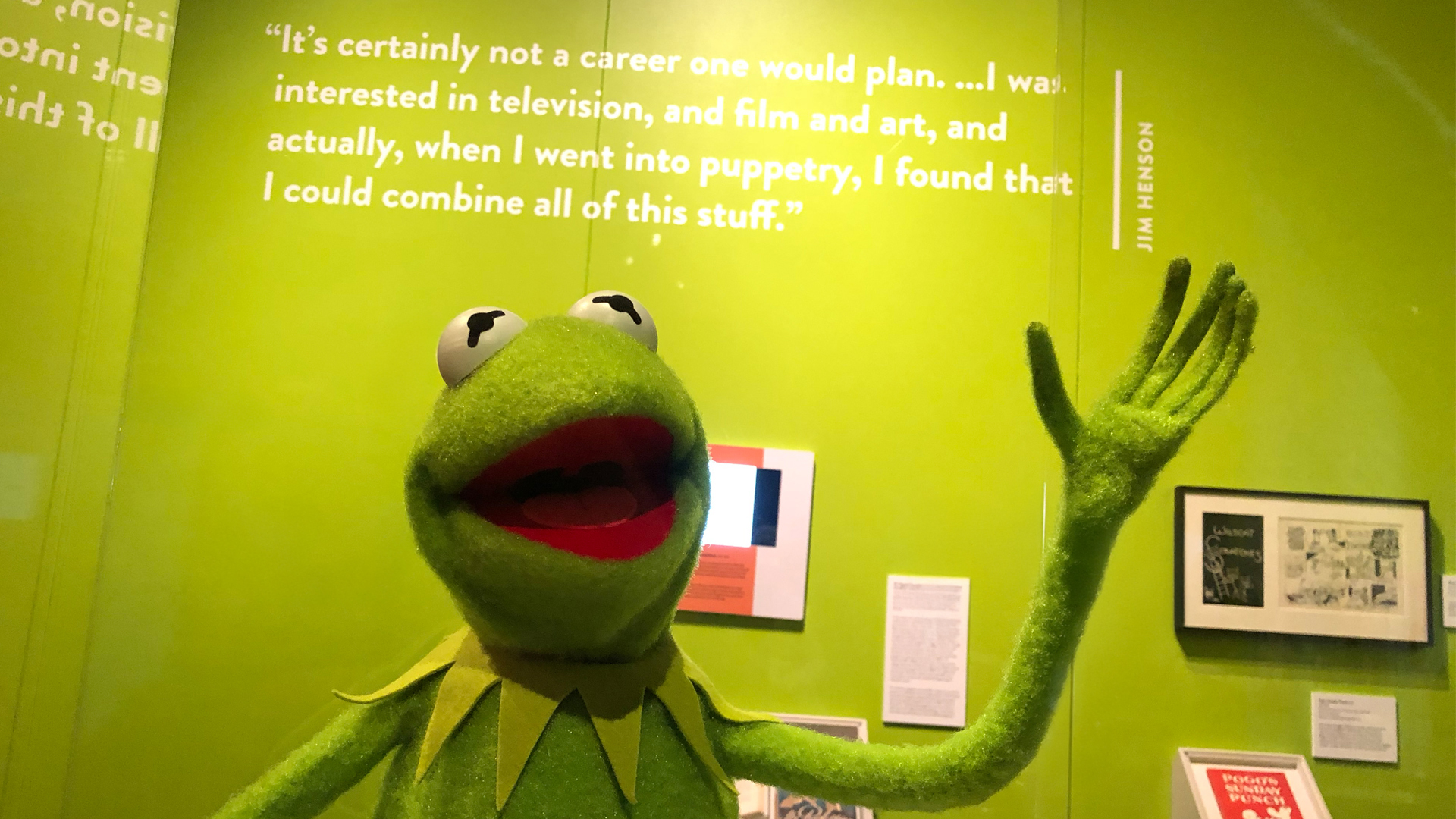

So some of the characters, their arms, for example, were the thumbs of gloves. The sleeve for the original Kermit (which is now at The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History) is a leg of a pair of jeans that they just cut off.

Some of that was expediency, you know, “We need a tube of fabric. This is in the rag bag. I can cut it off and I have a tube of fabric.”

But some of it was a style choice as well.

Karen: Jim recognized his drawings as just part of the creative process. They were not the finished product. What was going to be the finished product was what ended up on the screen.

He needed to get the information down. It was his “draft” of the character, so that could be built, so that it could be then performed on screen.

It was really important that what happened on screen was perfect, but the process of making the character was not for presentation.

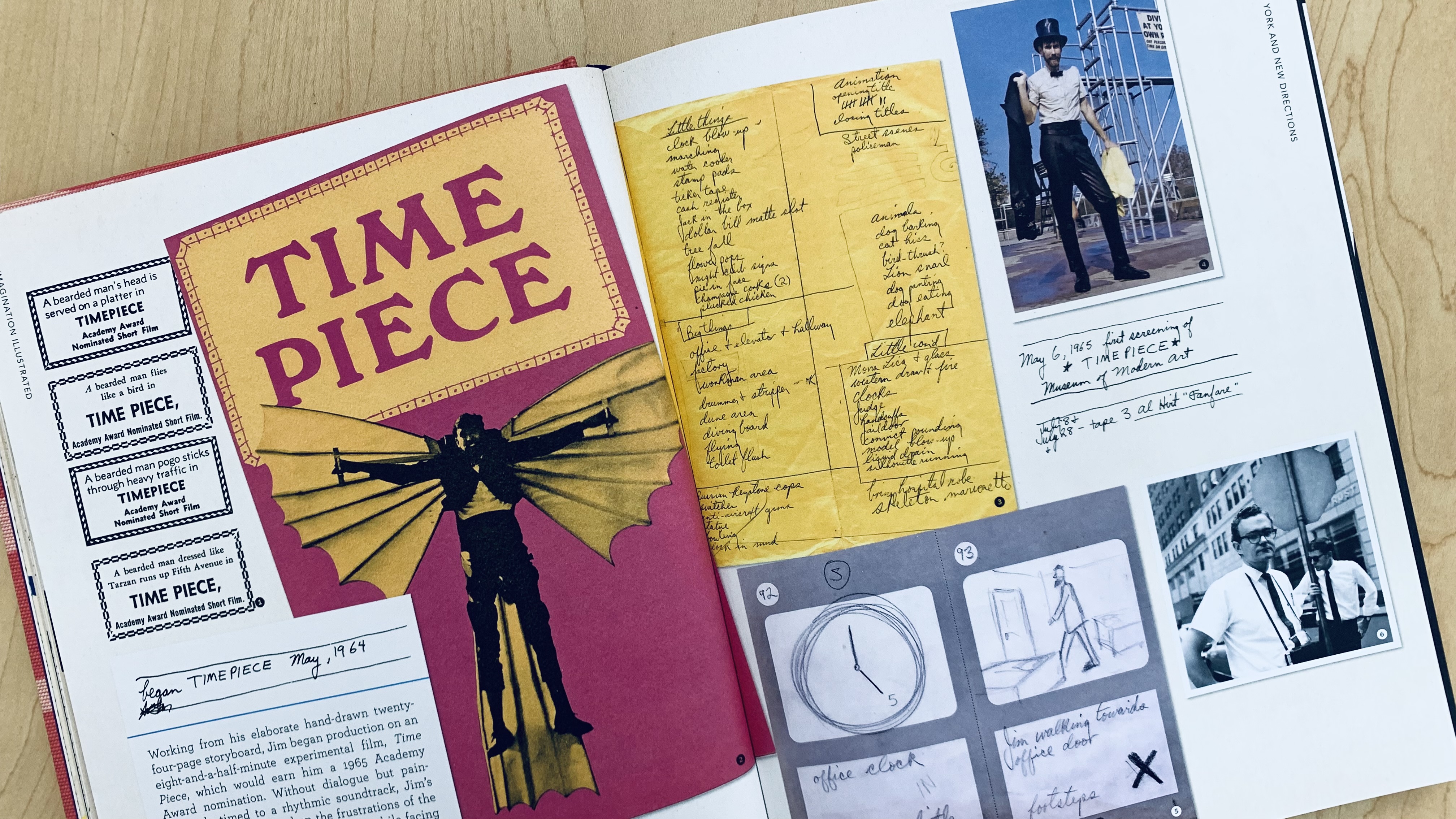

We do have quite a bit of artwork that Jim did in the 60s as presentations, whether they were storyboards that he did for commercials, storyboards for the films that he did for Sesame Street, or presentation pieces.

He was trying to sell The Muppet Show.

He was trying to sell a Broadway review show.

He did much more careful artwork for those.

They were much more carefully lettered. they were much more carefully colored. They had cleaner drawings. They were still in a cartoon style, but they weren’t jottings down because they were what was going to be presented.

He was trying to sell something with these images, so he was more careful to make more polished artwork.

You know, the character designs, the doodles, things like that were really just part of the production process.

He did take life drawing classes and regular fine arts classes at the University of Maryland. That was an important part of his graphic training.

And he did nicely in them. They’re perfectly nice model drawings (the kind of thing that anybody does in college art classes) but that wasn’t really his strength.

Jim’s Character Designers

Karen: In the 1970s, he started relying more and more on other artists to do the polished designs of the characters and, particularly, Michael Frith.

Michael Frith is just the most spectacular draftsman, a wonderful artist. He does very complete drawings. He gives the builders much more information than Jim ever did.

He was working for Random House, working with Dr. Seuss and what have you. He, in the early seventies, started doing Sesame Street books. That’s how Jim got to know him.

He was brought in to start designing characters in the early seventies.

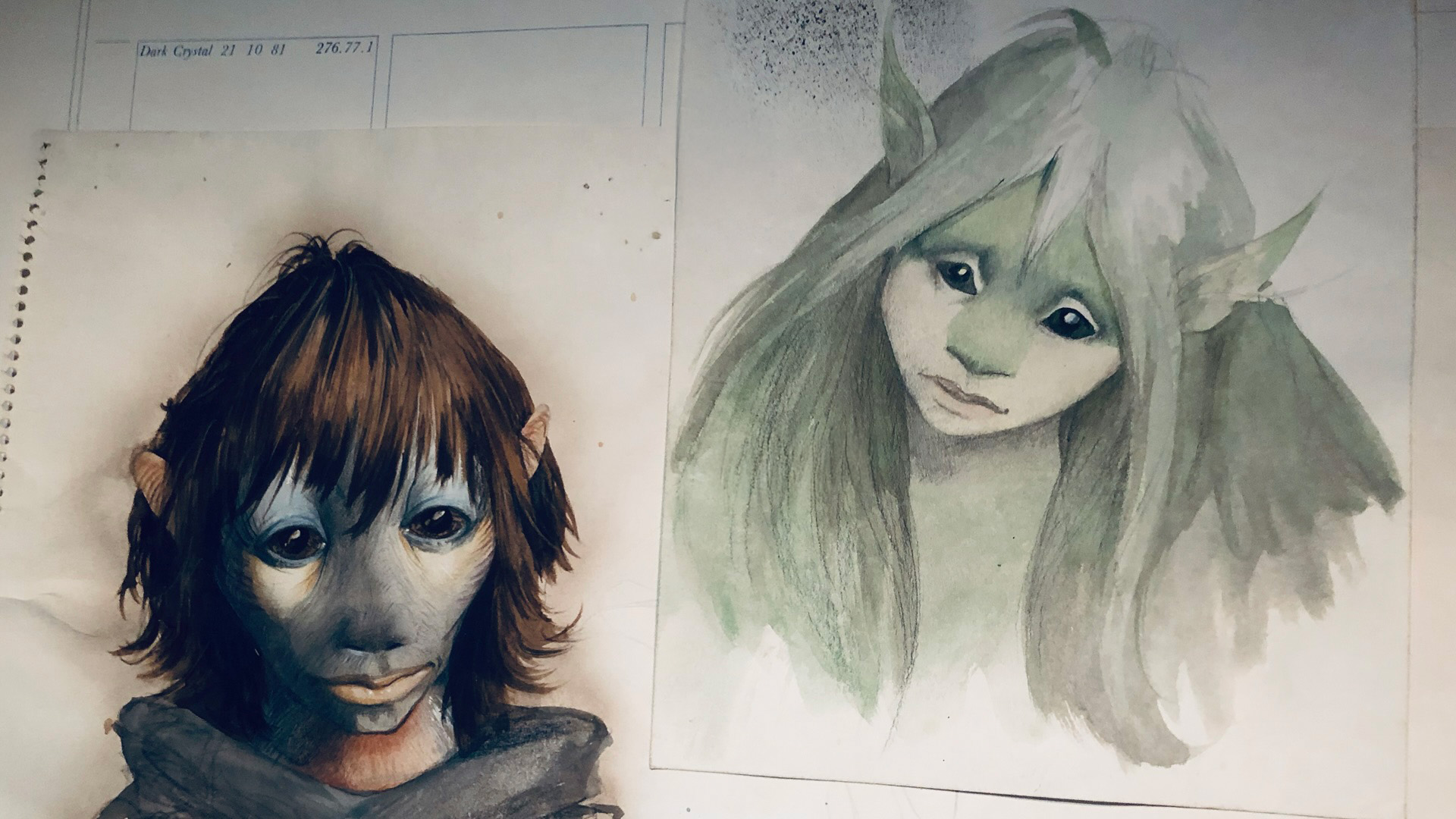

He did the (sort of) finished designs for many of The Electric Mayhem characters, tons and tons of Muppet Show characters and then, all the Fraggle characters, for example.

And so the builders were given something so finished in general. I mean, they’re given a lot of leeway in terms of colors and materials and how they’re going to affect whatever it is they see in the drawing, but his drawings were much more polished than Jim’s.

Chris: And the same goes for Brian Froud.

Karen: Of course.

Chris: There’s this very resolute visual style. It’s resolute before it even goes into the third dimension.

Jim Henson The Director

Chris: Something that is so challenging to me to try to get my head around is the idea of Jim as a director.

People talk about his direction style as being pretty hands off and enigmatic in a way. It seems like you just knew when it wasn’t good enough, but you wouldn’t get a lot of very direct critique.

Do you think that’s accurate?

Karen: Well, I was never on the set with Jim Henson, so I can’t really speak from experience, but my understanding is that he trusted his colleagues.

He trusted the artists that were working with him.

So if he indicated that something wasn’t working and that they should try it again or try it a different way, he gave them room to figure out what “better” might be.

But the interesting thing about the kind of puppetry that Jim developed, and of course he can be credited with really changing the way puppets were used on television, is that every single puppeteer, to a certain extent, is directing themselves when they’re looking in the monitor.

They’re watching their own performance while they’re performing and they’re making all those choices about how they’re going to turn their head, what kind of expression they’re going to make…

Because they’re watching themselves on the monitor, they get the immediate feedback.

So they don’t have to wait to hear from the director that something didn’t work or that their head wasn’t in the right place or something…

And so, maybe, Jim didn’t need to be as vocal about things because he wasn’t the only one seeing the performance. They were seeing it themselves.

Controlled Chaos

Chris: And, also, there’s just a, sort of, “controlled chaos” aspect to everything. Controlled chaos, encouraging each other to upstage one another, just all part of the deal…

And I’m sure as the word got out about this creative team, when you’re interviewing to go work for them (or however the hiring process worked) you already kind of know what you’re getting yourself into.

There’s a filter built in to whether you want to be part of this culture or not.

You’re probably not going to attempt to join up if controlled chaos isn’t your thing.

Karen: Pretty much everybody that wants to work here, work with these people, it’s because they’ve seen the final result on the screen and they think, “How could I be part of that?”

Joining The Jim Henson Company

Karen: For me, I worked in the fine arts business.

I worked for Christie’s Auction House and our office was down the block from The Muppet Workshop.

I would see people walking up and down the street with jackets with Kermit the Frog on the back.

I thought to myself, “Wow, how could I work with Kermit the Frog? I love the Muppets. That would be so cool. What could I possibly do for them? I’m not a puppeteer. I’m not a puppet builder or an artist.”

I lucked out that there was a role that fit my skills and abilities and I was able to join the troop.

I was hired in 1992 not too long after Jim died. Jane Henson had established The Jim Henson Legacy Group to preserve and present Jim’s body of work.

She was working with some of his colleagues and some of the people in the company to try to make sure that the work that he made during his lifetime continued to be presented and that people could learn about his story.

She felt like there was a need to bring in a full time person to do archives because that had always been a small thing that was part of the public relations department, etc.

When I was hired, there was a small collection. But we went back into storage and started pulling all the boxes and everything and really creating the archives.

Jim’s Red Book Blog

Karen: It was about nine, eight or nine years later, and we had done exhibits and I had discovered there’s all this stuff, not just about Muppets, not just about Sesame Street or Fraggle, but all these other things that I didn’t know about, particularly the early years.

We were trying to build up our web presence (This was about 2010.) and I said, “Well, there’s this journal, this ‘Red Book’ that we used internally as a basis for tracking the history and figuring out what we wanted to document in the archives.”

I don’t know how new Twitter was in 2010, but I thought his entries in his Red Book journal were almost like tweets. The entries were just something that happened that day or something he appreciated. We could tweet those.

I was looking for ways to share the archives because it’s a private archives. People can’t walk in. We can do exhibits. That was one of the first things I started working on when I came was trying to do exhibits to get the stuff out of the shelves and where people could see it.

So I said, well, then we could have the Twitter connect back to a website. It’s not, you know, brain surgery.

[LAUGHTER]

And then I could tell people about whatever it was that Jim was noting in his journal and why it was important and what it meant to the rest of his work and show off some stuff from the archives, some artwork and photographs and things.

I did that for about three years. I curated about 750 entries.

What was great was I was able to bring in guest bloggers.

There was a piece about when Jim Henson was snowed in and developing the Dark Crystal. Cheryl Henson was with Jim at the time and so she explained about her experience. That was great.

Jim talks about hiring Connie Peterson to create and run the creature shop for Labyrinth. And so Connie wrote about her experiences for me.

I was talking about that show Starboppers that never happened and Ron Mueck, who’s this world renowned contemporary artist, he wrote about his experience as a young artist working on that as well.

It was really a great opportunity to bring in other voices and to document people’s experience.

Chris: That’s so very cool.

Puppet Preservation

Chris: Can you tell us about puppet preservation?

With so much of it being foam rubber, that is, of course, a ticking clock.

…a very quickly ticking clock!

Karen: Well, as you mentioned, these puppets are made of very transient materials. They’re made of foam and latex and glues and things like that, that self-destructs.

Because these were made as production pieces, they were not made as items to be saved, so preserving them for museum exhibits is a bit of a challenge.

The soft foam puppets are a little easier.

Our creature shop here has developed techniques, partially with consultation from The Smithsonian’s conservation lab, and then the Center For Puppetry Arts has their own conservation lab, and they replace a lot of the foam with archival foam.

Those puppets are no longer performable because you lose that flexibility, but they are stable.

The latex is tougher.

But the Center For Puppetry Arts, they have a conservator named Russ Vick, who has developed a lot of techniques for preserving the latex, stabilizing it, if not fixing it.

He worked with some chemists at Georgia Tech to come up with some different combinations of things.

And so everybody does what they can.

You know, you can just have something in a box in a dark closet in a stable environment, and it might last longer, but then nobody gets a chance to see it.

So we really want to put it out there.

The Museum Partners

Karen: But that’s part of the reason that we partnered with all these museums.

We had this very large collection of historic puppets that belonged to the Henson family. We had done a big inventory in 1999 to determine which puppets should be deemed as historical and should basically come out of the storage that is run by our production side and become puppets for exhibits and museums.

We talked about building a Jim Henson museum, but it clearly was going to be a huge burden to do something like that.

And we didn’t really have the infrastructure within the company. We’re a production company, so we don’t really have vaults and things like that for climate control to, to really maintain these puppets the way they should be maintained.

So that’s when we sought partners in existing institutions.

Museums have the infrastructure to care for these things. They also have the, I want to say “infrastructure,” but it’s sort of outfrastructure, to bring people in and give them a chance to see these objects and experience them.

The family donated close to 500 objects to The Center For Puppetry Arts as they were developing their new museum (That’s in Atlanta). The museum is half world puppetry, which is something Jim supported and was fascinated by, and then half about Jim Henson. And they do changing exhibits and special exhibits as well.

So that’s been a terrific partnership, and they also make their puppets available to lend for other exhibits and things, which is great.

The family also gave about 350 objects to The Museum Of The Moving Image here in New York.

Our first travel exhibit ended its tour at Museum Of The Moving Image. It was a really great combination – Henson and that museum.

Jim really was broadly described as a moving image artist because he was interested in all aspects of the moving image. So it was really a perfect place to tell his story.

After the exhibit, they said, “We will dedicate space to Jim Henson if you will give us a collection.”

It seemed like a match made in heaven, so the Museum Of The Moving Image got the collection.

We already had a long running relationship with The Smithsonian Institution, The National Museum of American History.

The Smithsonian’s Traveling Exhibition Service had toured our Jim Henson’s Fantastic World exhibit that I had curated with our Legacy Group.

We lent puppets for various exhibits there. Jim had given them a Kermit in the 1980s and had other puppets on loan in his lifetime.

He was from Washington, DC. It meant a lot to Jane Henson to have Jim’s original puppets from those Washington years at the museum.

We also wanted them to have some other major characters in their collection so that they could, again, represent Jim’s story in their museum. So they have a much smaller collection, but that is featured in their Entertainment Nation exhibit, which is their new, big history of American entertainment.

There’s a dedicated Jim Henson case there that has rotating characters through it.

There are also characters from Sesame Street in the children’s entertainment section, so that’s great.

And then finally, when The Academy Museum in Los Angeles was being built, I knew the curator. We had worked with her before and we saw the prospectus and everything and said, “Oh, gee, really, we would like to see some of Jim’s work in that museum as well.”

Karen: So the family gave about 75 objects from The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth and a couple other film projects to that museum.

So it’s really worked out beautifully:

We have Jim Henson, puppeteer extraordinaire, represented at the Center For Puppetry Arts. Jim Henson, moving image artist, at The Museum Of The Moving Image. Jim Henson, American icon, at the Museum Of American History in Washington and Jim Henson, filmmaker, at The Academy Museum.

And it’s, in my mind, better than having one museum because we’re out there in lots of different places.

Chris: And, certainly, for the fans because it’s more accessible that way, geographically.

Karen: And the great thing about, for example, The Museum Of The Moving Image having such a big collection is they were able to create this travel exhibit.

Imagination Unlimited is the name of the exhibit. It just opened this past weekend in Peoria, Illinois and that tour is coming to its end and it’s going to be reorganized for an international tour.

Chris: That’s great! I was going to ask you about Muppets going overseas, if that was on the horizon. That’s exciting!

Character Design Evolution

Chris: Can we talk about some of the turning points in the evolution of certain character designs?

For example, Miss Piggy looks so dramatically different now than she did when she was just an almost background character. (It wasn’t even Frank Oz performing her, right?)

Fozzie Bear, of course, has changed dramatically from this sort of somnambulistic character to how we know him today.

Gonzo, of course, cosmetically, has changed significantly.

My theory would be that the performer had some role in the actual graphic design changes to those characters.

I understand that part of that too, is that sometimes the puppets just get worn out and it’s time for a rebuild.

And so it’s like, “Well, if we’re already rebuilding it, let’s just make some tweaks.”

But could you could help to enlighten us about the character design evolution?

Karen: Well, I think that you really hit it on the head when you talk about the performer. I think the evolution of the characters is mostly from the performer.

They’re not building the character, but, certainly, the personalities of the characters are developed by the performers. As they work with the character longer and longer, it takes on a deeper and richer personality.

Miss Piggy and Fozzie Bear are Frank Oz characters. The more he worked with them, the more layered they became.

And, of course, Gonzo as well. He’s Dave Goelz.

Dave is such a fantastic performer and his connection to the character and his ability to add layers to the emotions and find those are what really changed the characters on top of really astute writers zeroing in on those changes.

Gonzo showing some vulnerability on The Muppet Show and a writer like Jerry Juhl saying, “That’s something that we can tap into.”

And then, of course, in The Muppet Movie, he becomes more soulful.

These puppeteers are also growing up and getting older and having more life experience and bringing that.

The change in the look of the characters – with Miss Piggy, you know, the more she grew and became an important diva, an important entertainer, the better everybody wanted her to look. And so there was an effort to bring out the best in her and make her look great.

The first Miss Piggy was just a pig puppet that they glamorized. Miss Bonnie Erickson put these beautiful eyes on her, gave her the gloves and what have you. And then as her personality developed, she wanted to look better.

They used to originally hand carve the heads and now they cast the heads out of foam. So her finish is maybe a little more polished.

With Gonzo, that original puppet was this puppet from The Great Santa Claus Switch that was a hand carved thing and his nose was very fragile. (Of course, they’ve found ways to make a puppet that is not going to fall apart so easily.)

Sometimes, if they want to be able to put more mechanisms in the heads to change the way the eyes could be more expressive or something, they might have to adjust the shape of the head in order to accommodate those mechanisms, although usually that’s not the case.

And I think so much of it happens, not by committee. (There are no meetings or whatever.) It’s much more organic in terms of what the performer is doing, what the writers are doing, and then the leeway that the people in our Creature Shop are given to develop the characters.

Chris: Right. Yeah, that makes perfect sense. And that’s consistent with everything else that you’ve shared here.

The Historical Record

Karen: You have to be careful though.

I’m a historian and I use the documents and what have you to figure out what the historical record is. I build like a detective. You know, you build your story and you figure out what happened.

And I have, on a couple of occasions, when Jane Henson was still alive, said, “This happened.”

And she said, “Well, no, actually it happened this way.”

And, of course, she was there.

And I’m thinking, “Hmm, I have documents that show it happening this way. Maybe she’s not remembering.”

(Except for Jane remembered everything.)

And then, three years later, I would find another document that would support her version, and fill in the gaps that I wasn’t seeing in the documentary record.

It’s hard because people’s memories are faulty and they don’t necessarily remember things exactly the way they happen but the documentary evidence might be incomplete.

So you have balance the two.

That’s why it’s good to do interviews and talk to people and get their versions of the story and then try to piece it all together.

Chris: Yeah.

The Jim Henson Legacy

Chris: There’s a really magical thing about that because the challenge increases in complexity as people leave us, right?

So there’s something really profound about that work because in a way it is a project of immortality.

Karen: I have to credit Jane Henson with having the vision after Jim passed away to create The Jim Henson Legacy Group to recognize the value of having an archivist come in and create these archives and to really push these kinds of projects.

Jane knew that Jim was beloved when he died and his work was beloved, but she also, I think, saw other artists who lost centrality to the common cultural awareness.

She didn’t want that to happen to Jim’s work. She felt it was important that it continued on.

When I was hired, I knew the Muppets, The Muppet Show, Sesame Street, but I didn’t know about Jim’s early work. I didn’t know about the commercials and his experimentation. I didn’t even know about the fantasy films particularly.

I get all the press clippings and so there would be clippings from an artist or some critic describing something saying, “Oh, wow, that was so imaginative (or so creative or so crazy), it was just like something out of the Muppets.”

That’s what they would say.

And then, over this period of time that I’ve been doing this (which is a long time) I’ve seen the shift and it’s now, “Oh, it seems like something that Jim Henson would have made.”

And so this man’s name becomes the synonym for creativity and innovation, and humor, and all those things, whereas it used to be people just used this generic “Muppets” term.

And I think so much of the awareness is the work that Jane set in motion.

…to do museum exhibits and books.

Jane and her children and the rest of the Henson family, certainly, they have all been incredible supporters of these museums and the book projects.

The idea of a Jim Henson biography was something that the family wanted to happen from the time he passed away.

But it really needed to be the right writer.

They vetted different people that would come to them with proposals and they finally allowed Brian Jay Jones to write the biography and gave him full access to the archives.

I like to think that Jim Henson’s Imagination Illustrated, my book, is the visual companion to Brian Jay Jones’s book (which came out a year later) because we were working from all the same material.

You can go through my book and it can give you the images for the things Brian Jay Jones is describing. And in some cases even, he’s quoting things from The Red Book and you can see Jim’s handwriting in my book. So it was really fortuitous that those two projects happened more or less simultaneously.

But getting that biography out was a huge step in setting Jim’s story in the public. Setting up these museums has been incredibly important in telling that story.

And now Ron Howard’s beautiful film…

Chris: Yeah.

Karen: …really is the icing on the cake.

And it’s reaching millions of people.

And so many people who might never come into a museum or might never pick up a book are going to see it on Disney Plus and get to see again that kaleidoscope of creativity and innovation and optimism that represents Jim Henson.

Chris: Yeah. That’s amazing.

Karen’s Unique Perspective

Chris: Well, that brings me to my last question.

You have such a unique perspective, this bird’s eye view perspective in a lot of ways.

When you think about his work, what are the common aesthetics and thematic components that you have noticed over the years?

There are some that probably most people would be able to identify, but I’m wondering if there’s anything that you have noticed, threads that you’ve been able to keep track of, identify over the years that you feel like people don’t talk enough about or maybe is unique to your position at the archives.

Karen: What I love is that Jim’s sense of humor comes through in every little aspect. Whether it’s the doodle that he did around something he was writing down…

He did experimental animation pieces and he did a short film called Drums West, which was to a Chico Hamilton drum track, and it’s just cut paper to the rhythm.

It’s completely abstract, but at certain moments when you hear a beat and you see what Jim did on that beat, it makes you laugh. And it’s this sort of inherent sense of humor that comes through in his work.

Even in his more serious pieces or the fantasy films, that is so important to his work.

You see it in the littlest things. You see it in his home movies, he’s winking at us and he’s having fun. And I think that that is such an important aspect of his work.

There’s some funny little things that show up that I love.

He liked two-headed characters. There’s the two-headed monster from Sesame Street who’s just such an amazing character. He was trying to do two-headed characters in the sixties for some commercials and he did like a push-me-pull-you type two-headed horse character for a project late in his life where he was trying to pitch a show about teaching English as a foreign language.

I think the character talked in different languages to each other.

[LAUGHTER]

I think he loved the idea of one being having two different kinds of ideas, just that back and forth, whether it was between Bert and Ernie or Kermit and Piggy or two heads of a monster or something.

I just thought that was something that’s really fun to see throughout his work.

And then this whole idea of understanding where ideas come from, how do we learn, how do we organize our thoughts?

The Red Book, of course, is his way of organizing a lot of his thoughts.

He did some experimental films in the 60s called Organized Brain where he was trying to visually represent how we think about things.

But I think that that comes through in, not just Sesame Street, but other things.

One of the very first ones like that is Visual Thinking, which he did for Sam and Friends, where the character’s trying to visualize his thoughts.

But that’s what Jim was doing. He was a visual thinker and he was trying to express himself in images.

…but not just images. Images with sound, with three dimensions, with music and all those other things…

Every Successful Art Career Is A Collaboration:

Get clear, relevant feedback on your work and personalized career guidance in our mentorship: The Clockwork Heart.

Never Miss An Episode:

Subscribe to this podcast on any of the major platforms (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Audible, YouTube) and join our email list for notifications about future episodes, courses, and mentorship opportunities.

It’s 100% free and we will always respect your privacy.

Credits:

I’m your host, Chris Oatley, and our production coordinator is Mari Gonzalez Curia. Our music is by The Bright Sigh (which is me) and this show is made possible by The Magic Box Academy.