Pixar Animation Studios was always known for quality storytelling, but in the early years of CG feature animation, they also set the standard for design.

CG feature animation was considered by many (even mainstream audiences) inherently inferior until the turn of the 21st century.

The fur and lighting effects in Monsters, Inc. were remarkable in 2001 (and they still hold up) but in 2003, Finding Nemo’s visual art finally and fully transcended the technological limitations of the new medium.

When interviewed about how they created such stunning imagery, the Pixar artists often cited their meticulous research.

Whether it was sketching professional ballet dancers in preparation for Fantasia’s dancing hippo sequence, living in Latin America for months at a time during development for Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros or hiring legitimate apex predators as models for The Lion King, Disney artists were willing to do whatever it took to achieve their characteristic verisimilitude.

…so why wouldn’t Pixar?

They got the Nemo art team certified for scuba diving. The Up artists flew to Venezuela to paint the world’s tallest waterfall. The Cars crew went on an epic road trip across the legendary US Route 66, the Ratatouille team wined and dined at fancy restaurants in Paris…

…and the Toy Story 3 team toured…

…landfills.

That’s right…

The Nemo people swam around a coral reef.

…and the Toy Story 3 people swam around in literal human garbage.

…but the movie probably wouldn’t have created the cultural phenomenon it did if the artists hadn’t been so committed to authenticity.

This is the second in a three-part lesson for artists who are ready to develop effective professional practices upon which they can depend for efficiency, consistency and quality in their work.

Today we’ll talk about the importance of working from reference – even when it stinks.

We’ll bust five common myths about reference.

…myths that if left un-busted put your portfolio at risk of landing in the trash.

Watch The Video (Or Read On For The Transcript):

Myth #1: “Reference Is Cheating”

About twenty years ago, before my relationship to zoos changed, I had an annual pass to one of the most impressive zoos in the US.

My art buddies and I met there several times a week to sketch the animals. They were all experienced animation pros and I was the sole amateur.

I went zoo sketching because I was trying to break in (to the animation industry, not the zoo). They went zoo sketching for the same reason my Dad runs his scales on trombone every night – even at age seventy-three (See lesson 1.3 in this series if you missed that bit).

My art buddies and I would sketch for a few hours then take a break to critique each other’s work. We also shared tips and resources.

One afternoon, by the gorillas, my friend Rafael Rosado (check out his amazing storyboard and comics work) let me borrow his brush pen which – because I’m a painter and not a draftsman – made my zoo sketches better.

(Some artists say tools don’t matter. But sometimes they do.)

I found a spot with a relatively clear view of a silverback. I crouched down and sketched him several times.

He wasn’t doing anything particularly interesting – just pacing in circles – repeatedly checking to see if the dusty truck tire was still there.

It was.

Meanwhile, a mom covered in sunblock and buckling under the weight of a NatGeo-sized camera was trying to get a photo of her son and his 500 pound cousin together.

The ten-ish-year-old kid stood maybe four feet from the glass and Mom told him to get closer. He only moved an inch or two.

Again, she urged him to get closer. He moved horizontally. She told him to go right up next to the glass. He obliged but clearly didn’t like it…

Now, before I finish this story about a gorilla, I need to make a side-note about sharks…

Shark movies are one of my “guilty pleasures.” However, there’s a strong argument that the “sharks-as-monsters” narrative has been very bad for sharks in the real world.

So when I tell you what happens with this gorilla situation, I’m not saying “gorillas are monsters.” I’m saying “This is what happens when you put live gorillas in cages for public display.”

Being scary is one of the silverback’s primary responsibilities to his family.

He was just doing his job.

…and, as nature intended, he scared the hell out of me.

I have experienced many different kinds of fear during my nigh-half-century on this planet, but rarely had I ever felt that original, caveman-brand, heart-pounding, all-five-senses-at-maximum-bandwidth, cowering-from-a-T-Rex-on-a-toilet kind of fear…

…until that silverback beat his chest and charged at the kid.

How can something so huge and heavy move so fast?

The ground shook as he ran.

The walls of the enclosure rattled when he slapped the glass with both arms.

It was very loud.

The crowd shouted.

The kid and I ran away crying.

No, I didn’t run away crying.

I just froze and stared at the silverback for a few seconds. (It took a while for my brain to catch up with the rest of me.)

Then I looked down at the brush pen sketch I had been so proud of before the encounter in question. One terrified line skewed off, leaving a trail of ruined gorilla sketches in its wake.

Now, except to say that I believe we should respect and protect animals, I need to leave the complicated topic of zoo ethics to the experts and focus on how this gorilla story helps us bust the myth that drawing or painting from reference is “cheating.”

One of the main indicators of an art myth is vague or shifting definitions.

So let’s take a moment to clearly define the terms “reference” and “cheating.”

When artists refer to “reference” they usually mean reference photos.

…but reference is anything the artist observes in support of the work.

Any “point of reference” is reference.

There are at least thirteen types of non-photographic reference – from color palettes to maquettes – that we cover in our courses at MagicBoxAcademy.com.

(You can join our email list at that link and we’ll notify you the next time we open for enrollment.)

For now, we’ll avoid overwhelm by focusing on just two types of reference: reference photos and direct observation (like zoo sketching).

“Cheating” can only happen in a game where two or more players agree, before the game starts, to play by the same rules.

Olympians agree not to use steroids…

Hide-and-seekers agree not to peek while counting…

Video game speed-runners agree not to edit their recordings…

…and when Olympians or hide-and-seekers or speed-runners break these agreements to gain an unfair advantage, we call it “cheating.”

So, if drawing or painting from reference is “cheating,” what’s the game?

Who made the rules and who agreed to them?

You can’t cheat if there’s no game.

If artists who use reference are “cheaters” then essentially every professional artist who has ever worked in animation, games, visual effects or illustration is a cheater, history’s greatest painters like Van Gogh and Monet are cheaters, the great illustrators like JC Leyendecker and Beatrix Potter are cheaters, The Hudson River Painters and all those dudes named after ninja turtles…

…all cheaters.

…but at what game?

You can’t cheat if there’s no game.

…and there is no game.

The claim that “reference = cheating” breaks down even further when you consider the relationship between drawing or painting from reference vs drawing or painting from memory.

Here’s what I mean by that…

There are two reasons I can, today, draw a silverback gorilla from memory:

1.) I have a lot of practice drawing silverback gorillas (as well as other animals) from direct observation.

…and 2.) I have a particularly vivid memory of what a silverback gorilla looks like because a silverback gorilla once ruined a page in my sketchbook with its OP AOE attack.

…so I can, today, draw a silverback gorilla from memory.

…but not without the use of reference.

…because to draw from memory is to draw from reference.

Whether you’re drawing something you saw two seconds ago or twenty years ago, you’re still drawing from reference.

It’s just a question of how long ago you looked at it.

To claim to be able to draw something without reference is to imply that you remember what the thing looks like. To remember what the thing looks like is to have seen the thing (or a photo of the thing) before. To have seen the thing before is to have a visual point of reference.

“Cheating” by way of reference is literally, physically impossible.

…so “cheating” by way of reference is literally, physically impossible.

…because memory itself is a visual point of reference.

Now, if somebody wants to invent a game about who can wait the longest between looking at a thing and drawing it, go for it.

…but that’s not an art game.

It’s a memory game.

It’ll also be the longest, most boring game imaginable.

…and it will never be totally fair because some memories are more vivid than others.

Myth #2: “Art From Imagination Doesn’t Require Reference”

I learned how to ride a bike about forty years ago.

I rode my bike all the time until college and started riding again in grad school.

I still love riding my bike.

A few of my friends are serious cyclists. One had an ad hoc bike shop in his apartment.

I’ve been to my local bike shop several times in the past year.

What I’m saying is I know what bikes look like.

…or at least I thought I did.

Recently, during a live demo for my students, I thumbnailed a few compositional ideas and one of them included a bicycle.

Because these were just initial ideas, I didn’t stop to gather reference.

…but the bike was so bad, it was almost unrecognizable. I got the wheels and handlebars right but the rest was just a mess of random triangles.

It would have been embarrassing if it hadn’t been so hilarious.

…so whether I have to wheel my current bike into my workspace or work from photos, I know I won’t be able to produce an accurate drawing of a bicycle without reference.

Artists who say they never need reference are saying they remember, perfectly, everything they ever try to draw or paint.

…but human memory is extremely unreliable.

(Look up The Central Park Five, The Loftus And Palmer Study and The Mandela Effect for further insights.)

…so why would an artist’s memory become more reliable as the complexity of their work increases?

You don’t need less reference as your art gets more complex, you probably need more.

…just like the Pixar artists I described at the beginning of this lesson.

You don’t need less reference as your art gets more complex, you probably need more.

If the myth that artists who draw and paint from imagination don’t need reference was true for anyone, it would surely be true for artists who work in fantasy art.

…and yet, fantasy artists use reference all the time.

Despite the physics-defying otherworldliness of Wylie Beckert’s work, she depends on reference to “keep the image grounded in reality.”

Laurel Austin combines counterintuitive animal references to create her unique creature designs. For example, during a live event at The Gnomon Workshop, she referenced rats, snakes and vultures to create a soul-stirring take on The Pale Horse Of The Apocalypse.

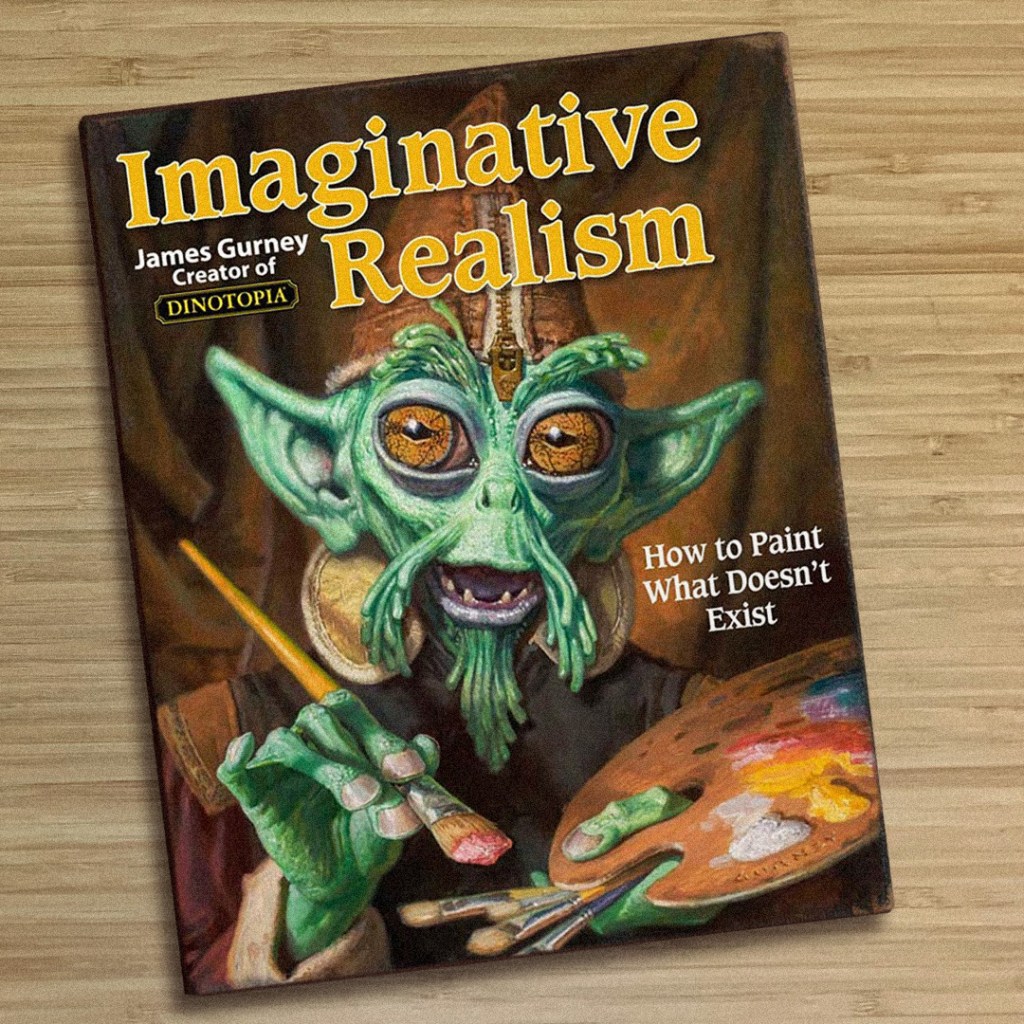

Dinotopia creator James Gurney builds sophisticated maquettes and scale models to get the perspective, lighting and anatomy right in his illustrations.

Is there any artist alive who knows more about how to draw and paint dinosaurs?

If anyone could justify shortcutting dinosaur reference, it’s James Gurney.

…and yet he doesn’t use less reference as his work gets more imaginative (not to mention ambitious), he uses more.

James Gurney believes so wholeheartedly that illustrators of imaginary subject matter could benefit from better reference, he wrote a whole book about it.

It’s called Imaginative Realism and I highly recommend it.

Some people say that pen and ink virtuoso Kim Jung Gi (RIP) could draw, from memory, anything he ever saw, without the use of reference.

…but that’s not accurate.

He said in an interview with Pang-e, “If that was true, I’d be somewhere else… …maybe NASA.”

He got very good at memorizing how to draw things through a process called deliberate practice. But he practiced with reference. By practicing this way from childhood onward, he memorized an extensive “mental library” of images.

As his mental image of a particular object developed, the more liberal he could be with composition and stylization.

…and sometimes he would “mash-up” details from one mental image and another.

To the uninformed, it seemed like he was just making everything up.

Kim Jung Gi was an extraordinarily skilled draftsman with an extraordinary imagination.

…but his skill and imagination were developed in the rigorous study of reference.

One of my favorite examples of what’s possible when professional visual storytellers work from thorough, relevant and accurate reference comes from the movie Annihilation (directed by Alex Garland).

As you can tell from the title, it’s a delightful little film about an incomprehensible, unstoppable, extraterrestrial power against which humanity’s only defense is nihilistic acquiescence.

It also has a mutant ghost bear.

Bring the kids!

Despite Annihilation’s relatively low-budget, the visual effects look more believable than some movies with double or triple the resources.

How did the Annihilation team do so much more with so much less?

In the insightful behind-the-scenes documentary Vanished Into Havoc, the artists discuss how reference was essential to creating the completely convincing creature featured in the movie’s central set piece.

…but before I begin describing the “zombear” sequence…

(“Zombear.” That’s a “zombie” but also a… …yeah, you get it…)

…I’ll issue a content warning.

I’ll try my best to keep the grizzly details to a minimum, but the next few paragraphs refer to PTSD and biological horror.

Natalie Portman’s team of scientists are sent into the region affected by the awful alien phenomenon I described earlier. The characters call it “The Shimmer.”

A character named “Sheppard” is attacked and abducted by a bear in the middle of the night.

Thorensen (in a captivating performance by Gina Rodriguez), has already grown paranoid because she knows Natalie Portman’s character is lying about something. Thorensen turns on the team, takes them captive in an abandoned house and antagonizes them in an attempt to discover the truth.

Just then, they all hear a voice screaming outside.

It’s Sheppard.

…except not really.

The bear that attacked Sheppard is back.

It enters the room and we see that it is now a zombear.

The Shimmer merged physical aspects of Sheppard as well as her time-of-death memories with the bear, resulting in what is quite possibly the most disturbing sci-fi creature design since HR Geiger’s Alien.

The concept alone is amazing, but I’ve watched the movie multiple times in 4k resolution and I think it’s accurate to call the visual effects work “flawless.”

The color, texture, light, shadow, proportion and movement in every lingering shot of the monster are completely convincing.

…because their reference collection left so little room for error.

The creature is computer-generated in every shot of the film, but the artists in charge of reference used techniques specific to the needs of each individual shot.

For shots that showed the actors and the monster together in close-up, the team replaced a highly-detailed hand puppet. The actors’ real-time reactions to the real-world reference puppet made the finished creature even more believable.

The team built a mechanical stand-in for wide shots where we see the whole creature. They wheeled that one around on a heavy platform so it wasn’t as agile as the hand-puppet (which was just the creature’s head), but that’s why they combined reference techniques and didn’t just use the same technique for every shot.

Finally, there were two versions of a stupid rubber suit like the kind you find in motion capture studios.

…like the kind Andy Serkis wore when performing Gollum or King Kong.

One sequence called for a stunt performer to charge across the room, knock over the actors who were still tied to chairs and pretend to attack Gina Rodriquez (she did her own stunts, BTW).

Even the biggest human stunt performer lacks the bulk of a zombear, so one of the two rubber suits had a sort of bear-shaped, rubber shell.

(I don’t know why it was purple, but it was. Maybe just to make the whole experience as silly as possible?).

The purple, foam shell helped to make sure that there was always enough physical space to fit the CG zombear.

…and that anything from the physical set that the CG zombear would later appear to collide with, would actually move in response to the bear’s motion.

Some artists believe the myth that reference is just for beginners.

Their mental image of a professional artist is an abstract, Platonic Ideal who develops skill drawing and painting fruit from reference every day for a few centuries until a b’halo’d art director appears above their workspace in a long, flowing robe and anoints them with the Scepter Of Professionalism so the artist can, from that day forth, draw or paint beautiful, believable images of anything they imagine and earn a fortune doing so.

…never again beholden to any type of reference.

…but professional artists hired to create imaginary imagery still use reference.

…often exhaustively.

Myth #3: “Reference Is All-Or-Nothing”

This is a new one to me.

…but just in the past month, I heard two different artists from two different friendship circles justify their decisions to waste time and energy struggling with problems that reference would have instantly solved because they believed in the myth that reference is “all-or-nothing.”

They each asked me for feedback on their work.

They each sent me a work-in-progress painting.

I asked each of them to send their reference as well.

They both said they didn’t have reference because their work was imaginary.

I told both of them about the time I took a twenty-three-hour road trip to the grand canyon and got lost just a few miles from my destination.

Frustrated, I canceled the entire trip and drove back home.

…which never actually happened, of course.

It was a sarcastic way of explaining that just because reference can’t take your work all the way, that’s no reason to abandon it altogether.

Certainly, a medical illustrator or a dog portrait artist might follow a single point of reference more directly than an animation, games or illustration professional.

…but artists who draw or paint from imagination don’t abandon reference, they synthesize it.

Dragons, for example, are dinosaurs with wings.

The more thoroughly you reference dinosaurs and real-world reptiles, the more believable your imaginary dragons will look.

…and before anyone replies with #notalldragons, let’s consider the most famous and beloved exception to this rule: Falcor from The Neverending Story.

I’m sure we can all agree that Falcor is far more than a mere “dinosaur with wings.”

He’s a “dogasaur” with wings.

Falcor is the exception that proves the rule.

He just has an extra point of reference.

…which the Falcor designers intended.

Reference is a vehicle for getting as close as you can to your destination – and the rest is artistic license.

Myth #4: “Reference Makes Art Look Generic”

Earlier I said I know how to draw a silverback gorilla from memory, but I didn’t specify what the drawing would look like if I did.

It would look like my zoo sketches.

…because that’s how I practiced.

If you asked me to paint a recognizable portrait of Koko or an on-model Donkey Kong from memory, I couldn’t do it.

…because the only gorilla I have memorized is a zoo-sketch-style icon.

I’ve watched a lot of videos about Koko and I’ve played a lot of Donkey Kong Country (I have a pile of broken controllers to prove it), but I need reference to draw or paint those gorillas accurately.

Try to draw an accurate likeness of a loved one without any reference.

Pick someone whose face is familiar to you.

…then try to draw an accurate likeness using good reference.

Compare the two drawings.

I can almost guarantee that the unreferenced portrait is more “generic.”

…unless you practiced drawing the subject’s likeness so many times you had it memorized…

Try this with anything – a car, a tree, a dog…

The one from reference will always be more specific.

…and in most cases, more believable.

My friend and former student Jenn Ely once described her job as a visual development artist as:

“It’s not A door, it’s THIS door.”

Myth #5: “The Internet Has All The Reference You’ll Ever Need”

When John Singer Sargent set out to paint Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (what some believe to be his magnum opus), he knew it would be a significant challenge.

Sargent biographer Evan Charteris said, “Never for any picture did he do so many studies and sketches.”

…but I often wonder if Sargent fully realized what he was getting himself into.

During this time, Sargent confessed to English writer Sir Edmund Gosse that he was considering giving up on art altogether.

Sargent didn’t specifically cite Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose as the reason, but it seems like curious timing (to me, at least).

Regardless, the painting presented the most unique reference-related challenge of Sargent’s career.

Because Sargent felt he couldn’t render the appearance of twilight as accurately in-studio as he could when working from direct observation, he set up a temporary workspace outdoors.

At the end of each day, he would prepare his brushes and palette and summon his costumed models who would stand by until the very moment the light was right.

Sargent played tennis with friends from his artist colony every evening, but while Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was in-progress, he would interrupt the game just before twilight, sprint over to the workspace, get his models in position, pick up his brushes and palette and paint for about three minutes until the light changed again.

He did this every evening for three months straight.

As the weather cooled, Sargent, as Charteris said, “muffled up like an Arctic explorer” and his models wore layers of warm clothing underneath their costumes.

When the roses in the background of the painting died, Sargent bought artificial replacements from a London department store and attached them, by hand, to the withered bushes.

In November of 1885, he had to store the painting in a barn because it was too cold to keep painting outdoors.

…but the painting wasn’t finished. In the Spring of 1886, he re-assembled the outdoor workspace and resumed his twilight painting sessions.

I think most of us would agree that this is an extreme example.

Fortunately, we now have digital cameras and the Internet to make relevant reference collection and analysis almost instantaneous.

…but my point in sharing this story is that many artists won’t even take the time to shoot a reference photo with the camera on the phone in their pocket, let alone build a maquette or ask a family member to pose.

Now, you might be thinking: “I don’t need to shoot my own reference photos, recruit models or build maquettes because I have the Internet! The Internet has everything I need.”

As a teacher, I do a lot of critiques.

I often ask to see the artist’s reference in addition to the work they asked me to critique.

…and, often, they don’t have any reference to show.

…and when they do, it often doesn’t match their work.

For example, one of my students was struggling with an illustration of a knight in a suit of armor fighting a dragon.

The student had reference photos of armor but no reference photos of a human figure posed like the character in their illustration.

Unsurprisingly, the character’s pose was the main point of failure.

One common excuse for a lack of relevant reference is that Google, Pinterest, YouTube, etc, didn’t have any images that matched the artist’s idea, so they just decided to “wing it.”

I can always tell when the artist is trying to “wing it.”

…and I can always tell when they properly prepare.

Of course Google/ Pinterest/ YouTube etc. won’t meet all of your reference needs. You’re an artist because you have original ideas in your head!

“Original” means they don’t exist in the real-world yet.

No, most of us don’t have the time and financial resources that John Singer Sargent had.

…but most of us have a damn camera.

…or a roommate or a mirror.

No point of reference will solve every problem in your art.

If you want to do pro-level work, then you gotta start using pro-level workflows.

…but it can help you solve all of the problems that would otherwise be a waste of your time and energy.

Art has enough struggle when you’re fully prepared.

…so why add needless struggle?

Do you really want to spend your time re-drawing that hand pose poorly for the twenty-third time in a row?

…or do you want to affect and connect with audiences through your ideas?

If you want to do pro-level work, then you gotta start using pro-level workflows.

Lesson 2.2. Homework:

One of the most famous classical illustrators is Norman Rockwell.

Some people don’t take his work seriously because it was unapologetically sentimental but, in my opinion, this is a bad reason to overlook one of history’s greatest visual storytellers.

One book I think every visual storyteller should have in their collection is Norman Rockwell: Behind The Camera.

It documents Rockwell’s dedication to reference and shows many of his most famous illustrations and the corresponding reference photos side-by-side.

Whether you can track down a copy or not, I also recommend checking out the reference-related posts at MuddyColors.com.

You’ll find side-by-side comparisons from Rockwell and many others at that fantastic site.

Get the Rockwell book and/ or visit Muddy Colors, look up some examples of how artists use reference, compare and contrast.

Your work will improve instantly if you just spend more time and energy closely observing more relevant reference.

Try it and let me know how it goes: support@chrisoatley.com

Next, In Part Three:

We’ll explore the relationship between practice and projects by applying a product design concept to the process for developing our visual stories.

Move on to lesson 2.3: De-Stress Your Creative Process (With This Classical Practice)

Questions?

If you have questions about this course email us via Support@ChrisOatley.com.

Every Successful Art Career Is A Collaboration:

Get clear, relevant feedback on your work and focused, personalized guidance for your art career in our newest mentorship: The Clockwork Heart

Never Miss A Lesson:

Subscribe via email and get each new lesson delivered to your inbox as soon as they become available. It’s 100% free and we will always respect your privacy…

Thanks!

Special thanks to Storybook Steve for providing the music in the video accompanying the lesson, to our Production Coordinator Mari Gonzalez Curia and to Content Producer Mona Lloyd for editorial contributions to this lesson.

Certain details in the stories featured in this article have been altered or remixed in order to anonymize the associated individuals.