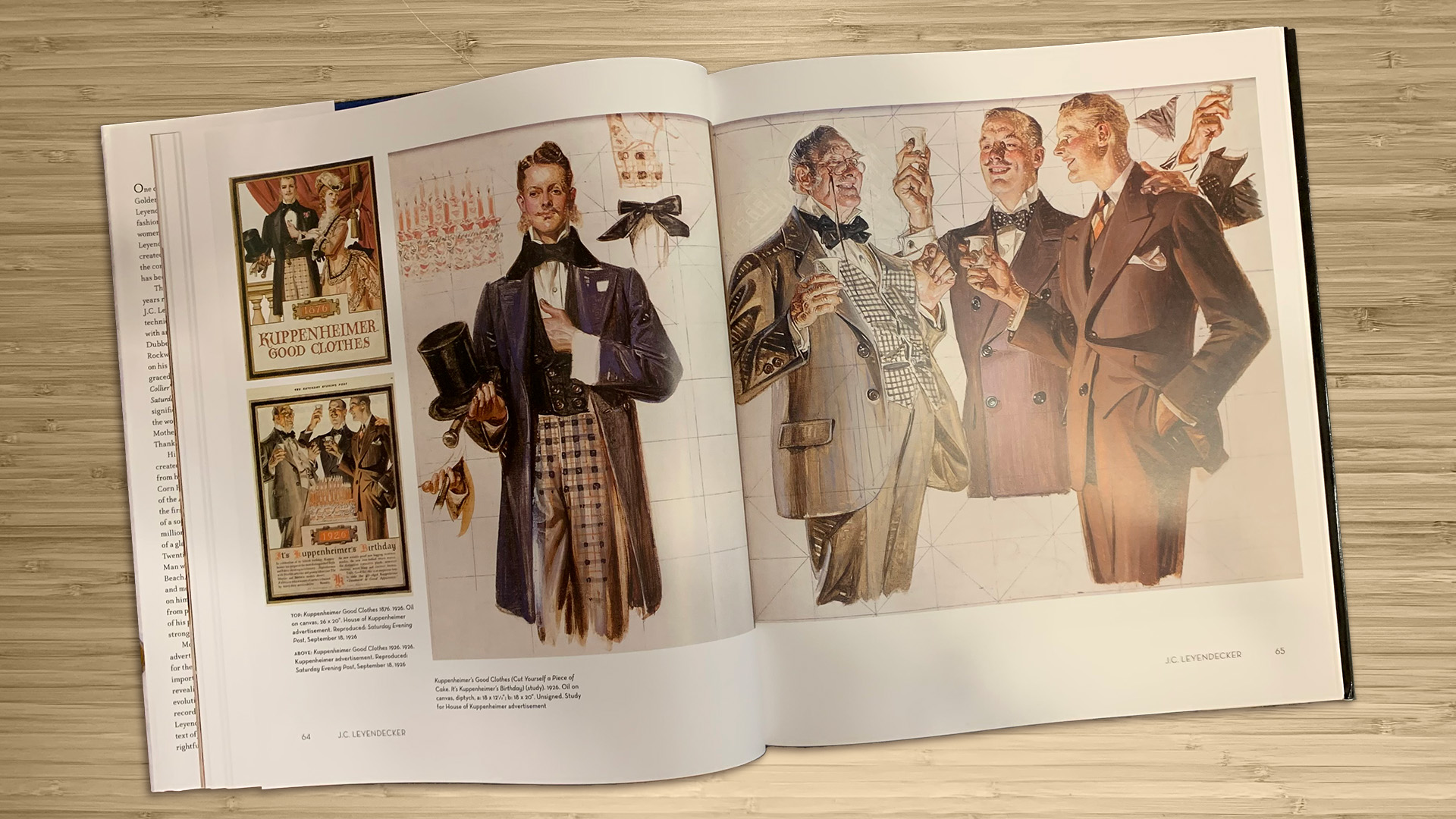

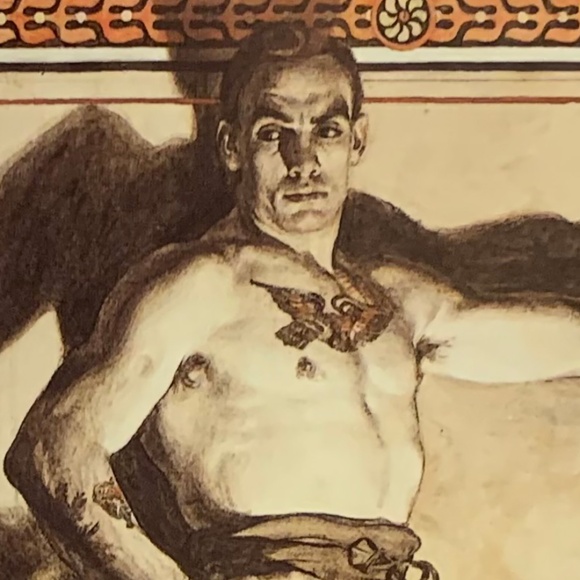

I leaned forward, my nose half an inch from the surface of J.C. Leyendecker’s “First Airplane Flight,” visually scanning the painting, mentally deconstructing the layers of his workflow:

The contradictory relationship between Leyendecker’s mechanically precise line art and subtle washes of underpainting…

That iconic, rhythmic pattern in his midtones…

The sharply stylized highlights and shadows…

An eccentric man with a silver beard and straw hat slid up next to me and asked:

“How’s it smell?”

I sort of laugh-snorted and explained my enthusiasm in hopes of engaging him in a collaborative geek-out.

“I’ve never seen one in person before.”

I resumed making out with Leyendecker.

“Yeah, he’s hard to find. I’ve only seen his work in person a couple times.”

“I can’t believe how perfect it is. There’s not a single correction.”

I exhaled as I spoke because, in my amazement, I kept forgetting to breathe.

Then, with his response, that mysterious, Scarecrow-Santa-Claus forever changed the way I think about art.

“Of course, there isn’t. He’d already painted it twice.”

My mind flooded with memories of all the Leyendecker value studies, color comps, and preparatory sketches I’d studied from art school onward.

That’s why Leyendecker’s work and the work of every other classic illustrator (Dean Cornwell and Norman Rockwell among them) on display that day was so confident and precise.

They literally prototyped their illustrations prior to creating what would be considered the “final” work.

…and why wouldn’t they?

They weren’t successful illustrators because they had good taste. They were successful illustrators because they hit their deadlines and delivered high quality work consistently.

But somehow, the rapidity of digital techniques often makes our modern day workflows less efficient.

Sure, it’s easy to open a blank file and start drawing, painting, or writing anytime we want, but without proper planning and preparation, our attempts at anything more ambitious than what we already have memorized lead to unnecessary struggle.

…which wastes time and energy.

…and increases the likelihood that we’ll get stuck.

Musicians record demo versions of their songs to save on studio time. Architects design buildings with foam core and/ or polystyrene models. Dancers and stage actors hold dress rehearsals…

Where is the benefit for digital artists who abandon the tried-and-true commercial art practices of value studies, color comps, preparatory sketches, and mock-ups, or for visual storytellers who begin without any sense of the end?

Today, we’ll talk about how to de-stress your creative process by investing more time and energy into the preparatory stages.

I’ll share three major benefits of this kind of prototyping and provide examples for each one…

Watch The Video (Or Read On For The Transcript):

Benefit #1: Prototypes Make Problem Solving Easier:

One of the main artistic benefits of investing more time and creative energy into prototyping (and preliminary work in general) is being able to discover and solve problems before you commit to the final work.

The further a project progresses, the more complicated and costly it is to change anything.

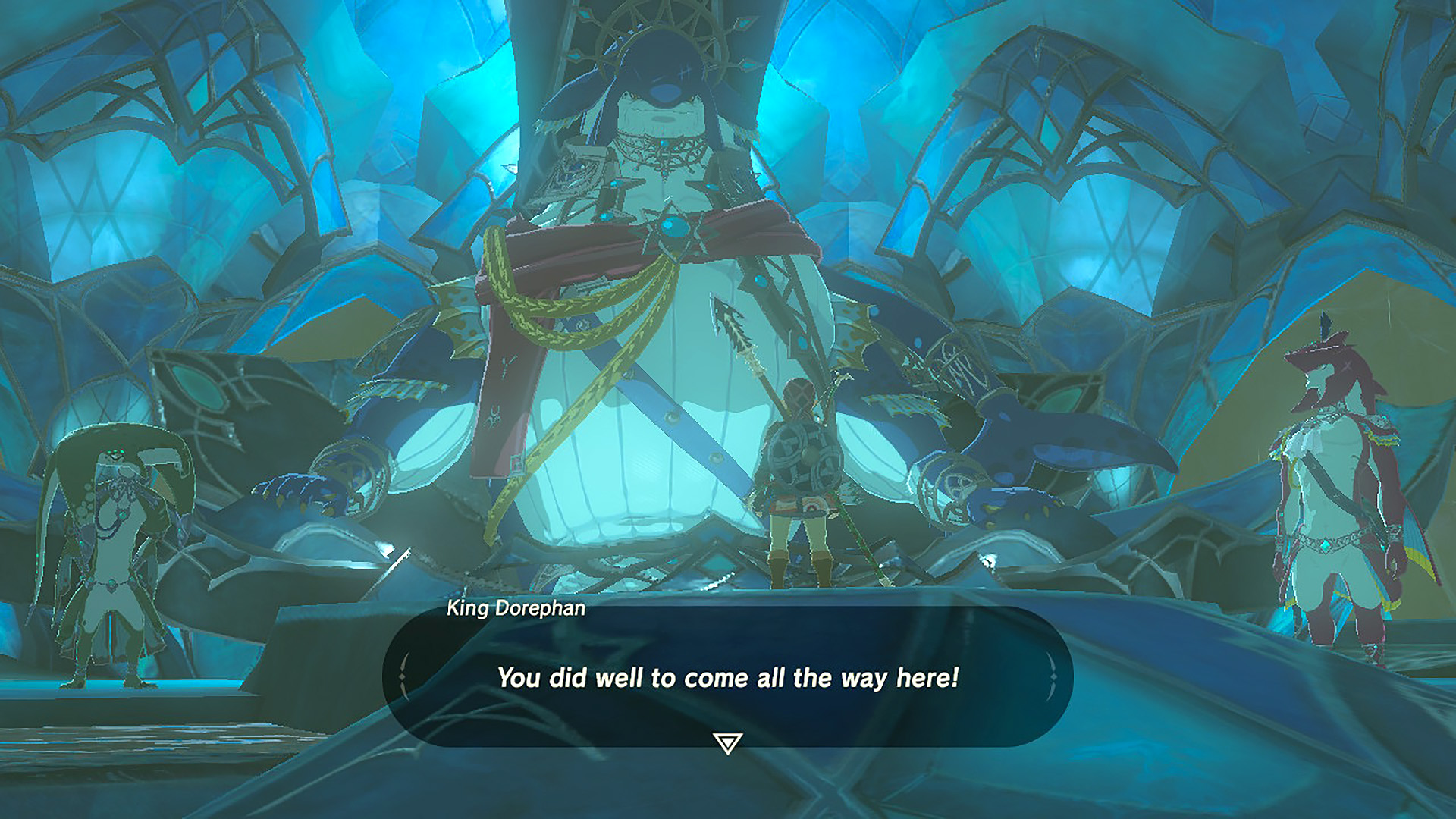

In 2017, Nintendo launched what is now widely considered one of the greatest video games of all time: The Legend Of Zelda: Breath Of The Wild.

The developers made history with an innovative, dynamic game environment where players’ actions, items and the world itself combine in complex ways to allow for a variety of emergent solutions and outcomes.

The developers call it “multiplicative gameplay.”

The friend who convinced me to buy Breath Of The Wild back in 2017 called it: “You can do anything!”

At the Game Developers Conference (a.k.a. “GDC”), the Breath Of The Wild leads revealed that their plan to reinvent the world of “Zelda” (and by extension, the world of video games in general) sent them back to the very beginning.

They began their work on Breath Of The Wild with a prototype in the classic, top-down style of its 1986 progenitor.

Valerie Precigout, author of Zelda: The History Of The Legendary Saga, explained that, in the prototype, “The 8-bit Link [could shoot] an arrow through a campfire to ignite the forest on the other side, then, [push] logs into the water using a tree leaf. None of this was possible in the first Zelda game, but it would be in Breath Of The Wild.”

When players have the freedom to combine actions and items in various ways, predicting all possible outcomes becomes nearly impossible. Ensuring that those outcomes were intuitive, meaningful, balanced, stable, and fun was, I’m sure, even more so.

The prototype helped the Nintendo developers discover problems and challenges that arise from multiplicative gameplay.

They observed various player decisions in the prototype, collected a long list of what-ifs and planned the development of the main game accordingly.

Breath Of The Wild director, Hidemaro Fujibayashi, explained that although the prototype was “the simplest way possible” to “experiment with the [multiplicative gameplay] mechanism,” it was essential nonetheless.

He continued, “This prototype did not include any puzzles. All we did was provide a situation involving a river and some trees. But, the user was then able to think for themselves and create a path forward. Through this kind of simple, primitive experimentation, we made the call of what to change and what not to change to complete the basic game design.”

Of course, the Nintendo developers needed a prototype for such a complex project, but independent creators and collaborators can still benefit, in essence, by following Nintendo’s example.

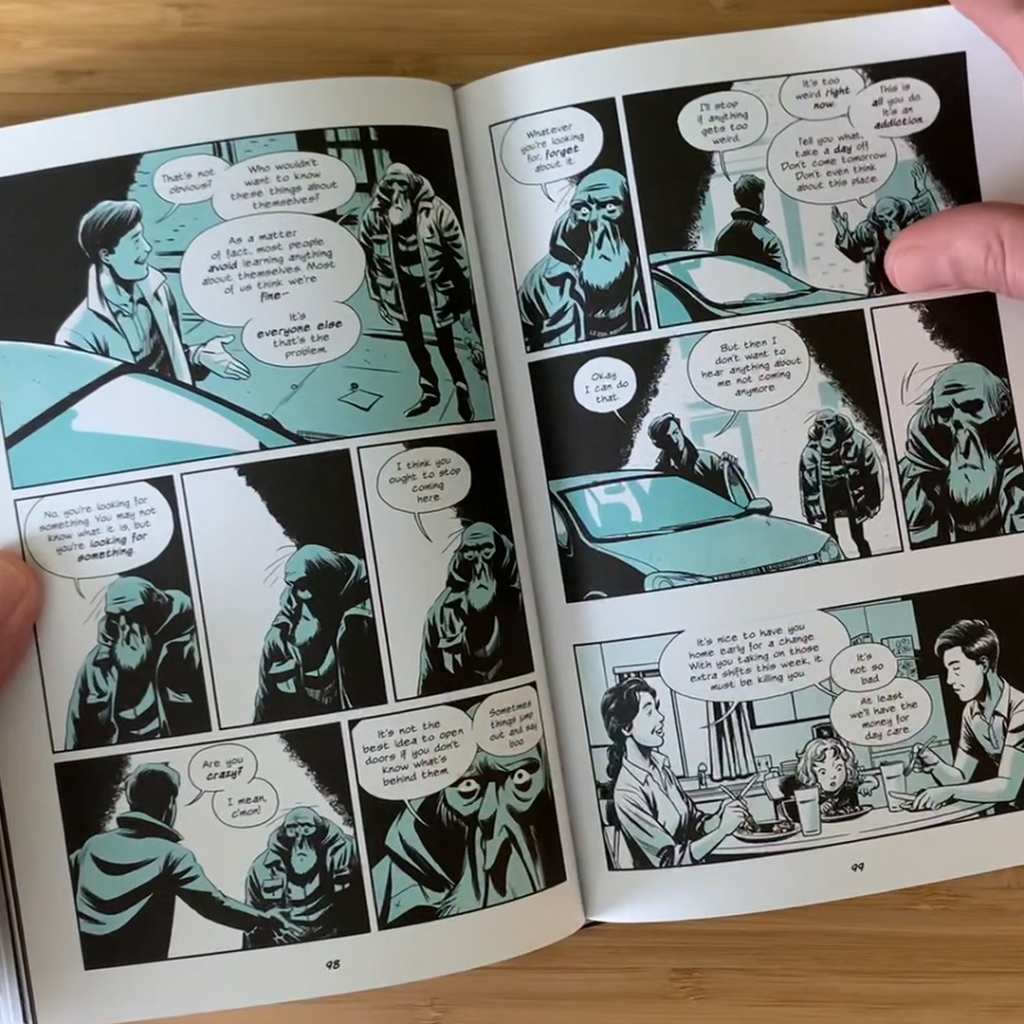

My friend and mentor, Brian McDonald, wrote the graphic novel Old Souls.

Les McClaine illustrated the book, and it was published by First Second.

One day, I was hanging out with Brian, and he got an email from Les with some work-in-progress page layouts.

We talked about how good Les is at page layout, and Brian said that’s because for every book he draws, he does the entire layout twice.

“Twice?!” I asked.

“The whole book?!”

Brian confirmed.

He later explained this process further…

“Once Les has laid out the comic, he instantly knows how to do it better and where he can make improvements. He has a better sense of story and how he wants to tell it. So then he lays it out again from the beginning, knowing more about where the story is going and how he wants to take it there visually.”

That’s when I realized Les McClaine’s first layout pass is a prototype that helps him solve problems in advance of the final work.

…and that got me thinking about how Les’ graphic novel process isn’t that different from the kidlit creator’s practice of creating book mock-ups called “book dummies.”

I don’t know why they’re called “book dummies,” but I assumed it’s because book dummies are literally the crash test dummies of children’s publishing.

…and that got me thinking about how the publisher that makes all of those “for dummies” books should make a book titled “Book Dummies For Dummies.”

…just because.

Anyway, I wrote to my friend, former student and former colleague, Shawna J.C. Tenney (Oh, hey! J.C.! …just like Leyendecker!) who wrote one of the Internet’s favorite resources on how to create a book dummy and asked her for a definition.

She said, “Book dummies are basically a pitching tool. They are a model of what your book will look like” sketches and text all laid out with a couple of finished pieces.

Author-illustrators use it as a pitching tool to find representation from literary agents.

When the author-illustrator already has an agent, the dummy is used to pitch the book to an editor at a publishing company. The dummy book helps a publisher see the whole vision of what the book can be.”

I asked Shawna if she felt like her book dummy process offered any other benefits beyond the pitch function.

She replied: “A dummy book really helps me understand the pacing of the story and where I can hide interesting reveals behind a page turn.

It helps me identify if there is a good flow in the illustrations, a good mix of spot, full page, and full spreads, and a good mix of ‘camera angles’ to tell the story.

It helps me see where I can tell part of the story with the illustrations where the words aren’t telling the story.”

Prototyping, as evidenced by Nintendo’s 8- bit Breath Of The Wild, Les McClaine’s page layouts and Shawna J.C. Tenny’s book dummies, proves essential for solving problems early while it’s still relatively easy to change things, thus removing frustration and overwhelm when we approach the final work.

Now, you might be thinking that prototypes are only helpful when working on big collaborative projects like video games and books.

…but prototyping will improve your individual drawings, paintings, and stories as well.

Prototyping will help you de-stress your creative process because you’ll avoid the frustration and overwhelm that comes with trying to solve every design problem simultaneously.

…but is prototyping really worth the time and energy required?

…because it sounds like a lot of work.

Benefit #2: Prototypes Multiply Your Time And Creative Energy:

Whenever I challenge my students to invest more time and creative energy into preparatory work, questions (and sometimes outright objections) about deadlines always arise.

…but digital artists and visual storytellers who are worried about wasting time and creative energy with preparatory work are missing the point.

The point of preparatory work is to multiply our time and creative energy, not waste it.

As we just learned, discovering problems early allows you to solve them while it’s easier and less costly to change your mind.

That benefit alone saves you time and energy, but when your preparatory materials are fast and cheap, so are your iterative solutions.

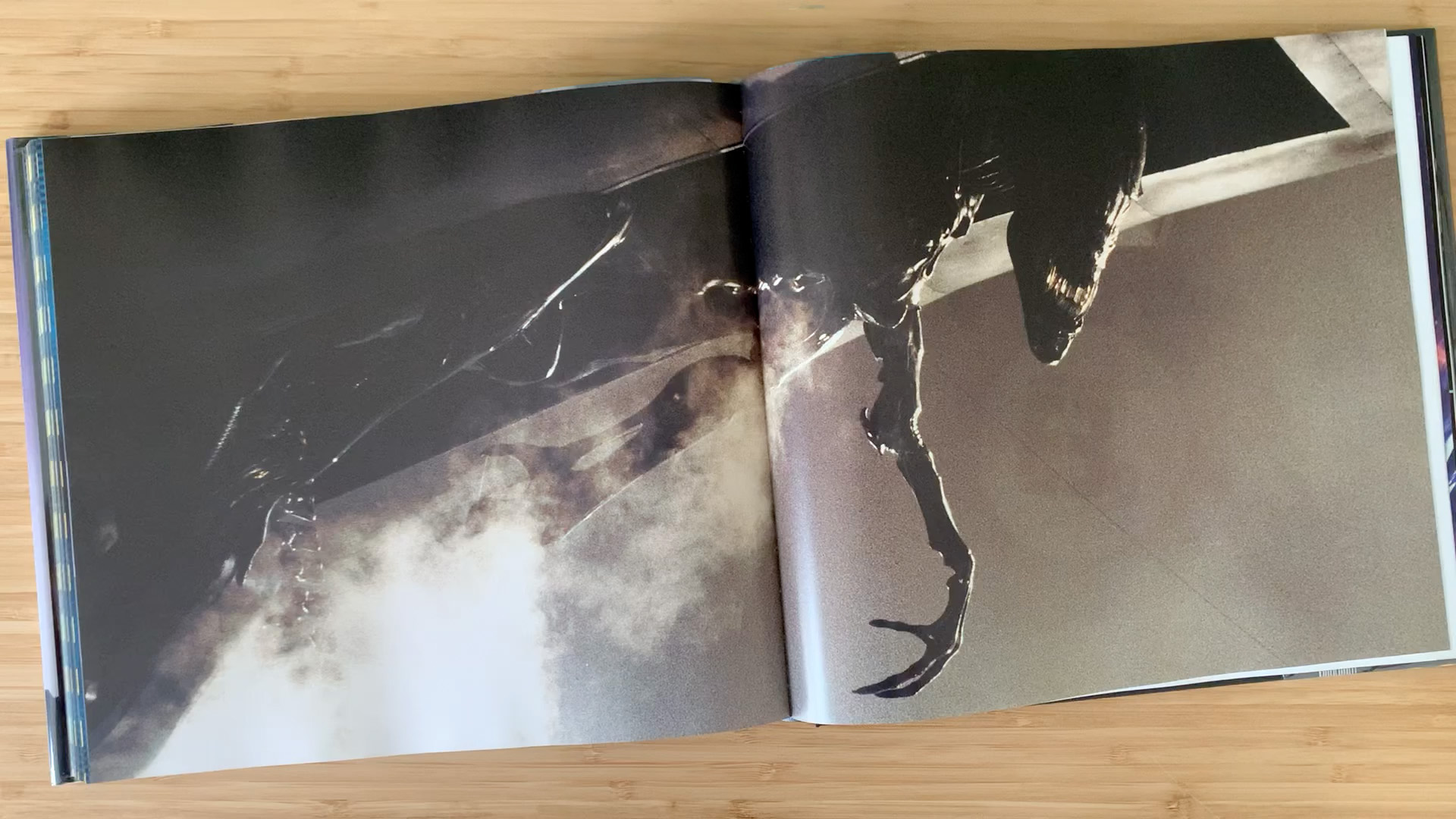

One of my favorite examples comes from the making of James Cameron’s 1986 Alien sequel Aliens.

(Oh, hey! 1986! …just like Zelda!)

The enormous-yet-agile multimodal and meticulously detailed alien queen animatronic featured in the film’s climax was a landmark achievement in the art of creature effects.

…but the prototype looked like garbage.

…literally.

As J.W. Rinzler recounts in The Making Of Aliens, “[James] Cameron and [Stan] Winston decided to create a low-tech proof of concept for the queen in the studio parking lot.

They rented a crane and built a body plate setup out of wood to hold two stuntmen. The crew formed a rough mock up of the queen using foam core and black plastic trash bags.”

…and here’s Stan Winston, “We put this garbage-bag queen alien together. Jim [Cameron] wanted to put two men inside the body to accomplish the four-limbed look, extend the body from a crane arm to hold it up, and puppet the legs externally.

Two of the men’s arms produce the queen’s small arms. The large arms were operated by one arm extended and holding on to something like a ski pole attached to some creature hands I had developed for another project.

Once we knew that the concept worked, all we had to do was figure out how we were going to build it for real.

The concept test proved that it could be done, basically, as a big puppet: Two people in a suit with animatronics.”

As you can estimate from archival footage of the creature artists at work, the film-ready queen would have taken weeks to sculpt, articulate, and assemble.

It took mere hours to answer most of their design questions via the prototype.

Imagine what could have gone wrong if they had skipped that stage of the process.

While it always seems to come as a shock to audiences when they learn that, yes, animation artists still use paper, it’s true nonetheless.

…but did you know that we don’t just draw on paper?

We also build messy maquettes to sketch our sets, props, and characters in 3D.

Even though most of my own work as a visual development artist is digital, I apply traditional techniques as often as possible.

If the perspective in an environment or the anatomy of a character is giving me trouble, I don’t just furrow my brow, hunch, and press harder with the stylus while spewing profanity…

…well, sometimes that’s the only viable solution, but most of the time, I get away from the computer and prototype “quick and dirty” solutions.

While I’ve never used garbage bags, I always have aluminum foil, copper wire, duct tape, Sharpie markers, and Play-Doh at the ready.

(Yes, I just gave you an excuse to go out and buy Play-Doh as a grown-up. You’re welcome.)

In The Art Of Up by Tim Hauser, there’s a photo of two artists building a paper prototype of Carl and Ellie Fredericksen’s living room.

(The artists are, unfortunately, uncredited.)

With the exception of the movie’s two iconic armchairs, (which were sculpted prototypes), all of the set dressing was just concept art printed orthographically onto flimsy cardstock.

How long does it take to print three pages of concept art and tape them together?

…and how many hours would the CG environment artists have spent tediously repositioning bits of set dressing to get the composition of the Up house right?

Cuphead artist Jake Clark prototyped the “Cala Maria” boss fight like a storyboard animatic (the kind you’d find in an animation pipeline), “using scanned-in scraps of paper and Adobe Flash (when it still existed) to work out the complex animation cycles, before [they ever thought] about cleanly animating anything.”

As good as the Cuphead animators are, they were smart enough to know that animating to a prototype, even one made from “scanned-in scraps of paper” would save time, energy, and what I’m sure would have otherwise become overwhelming frustration.

As the garbage bag alien queen, Carl and Ellie’s paper house, and Cuphead’s animated scraps prove, prototyping pays off.

…but you must keep in mind that the prototype is not the finished work.

The prototype should be specific enough to reveal and enable design solutions, but messy enough to multiply your time and energy.

Now, let’s return to the golden age of illustration and learn more about J.C. Leyendecker’s preliminary process…

Benefit #3: Prototypes Make Your Work Look More Professional:

Throughout this lesson, I’ve used the modern term “prototyping” as a catch-all for any kind of preparatory work in commercial art or storytelling.

…because digital artists and visual storytellers often struggle unnecessarily with problems that could easily be avoided by paying more attention to the practices of creative professionals in other fields.

I addressed a common objection: that there’s no time to invest in preparatory work because deadlines.

…and demonstrated how a focused prototyping process will multiply your time and creative energy rather than waste it.

Now, let’s consider the same objection from a different angle:

Would you rather be fast or good?

…because in order to be both, you have to practice one at a time…

…and in the correct order.

“Each published painting was the distilled product of a great amount of work.

Once satisfied with his pencil sketch of an idea, Leyendecker would pose models in costume and directly paint oil on canvas, sketching the figures in various positions until the pose was just right.

No matter how well Leyendecker’s preliminary figure sketches came out, he always painted a more refined final version after the model was dismissed.”

Leyendecker detailed his own workflow in a letter that has since been widely circulated:

“My first step is to fill a sketchpad with a number of small, rough sketches about two-by-three inches, keeping them on one sheet so you can compare them at a glance.

Select the one that seems to tell the story most clearly and has an interesting design. Enlarge this by squares to the size of the magazine cover, adding more detail and color as needed. You are now ready for the model.

First, make a number of pencil or charcoal studies. Select the most promising, and on a sketch canvas, do these in full color, oil or water with plenty of detail. Keep an open mind, and be alert to capture any movement or pose that may improve your original idea.

You may now dismiss your model, but be sure you have all the material needed with separate studies of parts to choose from, you are now on your own and must work entirely from your studies.

This canvas will somewhat resemble a picture puzzle, and it is up to you to assemble it and fit it into your design. At the same time, simplify wherever possible by eliminating all unessentials. All this is done on tracing paper and retraced on the final canvas.”

Of course, there wasn’t a single correction…

He’d already painted it twice.

While I’m sure we all agree that Leyendecker was a genius, he still had to earn that quintessential quality in every single painting.

He knew he was talented, but he didn’t rely on it.

He didn’t need to because he had a reliable workflow.

Digital artists and visual storytellers often seem to think of the preparatory work and the final work as separate things.

…and one, the latter, always has to take priority over the other.

I think J.C. Leyendecker, Norman Rockwell, Dean Cornwell, and all of the other legendary illustrators would disagree.

They’d probably say that all of the work is the “final” work.

The hole in the ground is just another part of the building.

The stop for gas is part of the trip,

Tilling the soil is part of the meal.

…and the prototype is part of the final product.

If you want to do pro-level work, then you gotta start using pro-level workflows.

Now, some of you are wondering about how to use reference most effectively, how to develop preliminary sketches or thumbnails, and how to synthesize everything using value studies or color comps

Those are all important questions for another time.

…but the answers are everywhere.

Online, of course…

But I recommend visiting your local library to get a physical book on one or all of the golden age illustrators. If they don’t have any, try the Renaissance, Mucha, Klimt, The Hudson River Painters.

Ya got options…

…and if you’d like more personalized guidance, you’re welcome to apply for my mentorship.

I’ve helped many artists make the switch from aspiring to professional over the past eleven years.

…but most importantly, remember this:

You are an exceptionally creative person.

You have new ideas and lasting passion and no shortage of curiosity.

You can figure stuff out.

If you’re willing to invest just as much creative energy into the preparatory work as you invest in what you previously considered the “final” work, your art will start to look more professional.

…and probably sooner than you think.

But even if it’s slow going, don’t worry.

Remember the words of my friend, former student, and colleague, animation visdev artist Jenn Ely: “Strive for good, and fast will happen.”

One comes before the other.

…and it usually doesn’t work in reverse.

Lesson 2.3. Homework:

From J.C. Leyendecker’s determined workflow, to the quick-and-dirty prototypes in Breath Of The Wild, Old Souls, Aliens, Up, and Cuphead, the role of prototyping is essential for crafting pro-level work.

With better investment in preliminary processes, you’ll avoid the frustration and overwhelm that comes from trying to solve every design problem simultaneously.

You’ll identify and iterate solutions for problems early while the work is still mutable, which will lead to significant gains in quality.

Your efficiency and endurance will increase as you establish consistent workflows.

…and your confidence will grow in sync with your clarity of vision.

Research the process of a classical painter or illustrator like Leyendecker, Rockwell, Cornwell, Mucha, or Klimt.

Check your local library for books on these artists or explore artistic eras like The Renaissance, Art Nouveau, or The Hudson River School.

Analyze the preliminary workflow and find examples of any or all of the major components:

- Reference (with Studies)

- Thorough Thumbnailing

- Value Studies and/ or Color Comps

…then, apply this step to your own process.

Pause often to take notes, document your process with photos or screenshots and, when the work is done, analyze the results.

In what ways did the work improve?

What aspects of your workflow will need to be improved next time?

If you’re a writer, do the same assignment, but adapt it for your chosen field, referencing the preliminary processes of screenwriters, graphic novelists, etc.

Next, In Lesson Three:

Every Successful Art Career Is A Collaboration:

Get clear, relevant feedback on your work and focused, personalized guidance for your art career in our newest mentorship: The Clockwork Heart.

Never Miss A Lesson:

Subscribe to the podcast on any of the major platforms (Apple Music, Spotify, SoundCloud, Google Play, YouTube) and join our email list for notifications about future episodes, courses, and mentorship opportunities.

It’s 100% free and we will always respect your privacy.

Credits:

If you have questions about this course, email us via Support@ChrisOatley.com

I’m your host, Chris Oatley, and our production coordinator is Mari Gonzalez Curia. Special thanks to Mona Lloyd for editorial contributions to this episode.

Our music is by The Bright Sigh (which is me) and this show is made possible by The Magic Box Academy.

Remember, my friends: You’re a better artist than you think.